The Online Weather World Should Take a Chill Pill, Before an Actual Disaster Strikes

Posted by @islivingston and @brendansweather

Weather is big business. A roar of competing voices has been increasingly evident lately, and more is likely to come. It's an odd mix of commodity and potential disaster. The science -- while moving forward at a continual great speed -- is still fragile, and the communication effort can be lost in an ever noisier world. The worst is when that process is egged on by those who should be the most careful.

We've seen both ends of online weather discussion: From the folks who just wanted to chat about snow and storms when doing so online was considered weird, to the innovative products transforming weather display, interactivity, and dissemination today.

The need to sell harder is apparent everywhere. For clicks, organizations seem to run with just about anything.

If it's not the Polar Vortex getting ready to devour you, it's likely the Pollen Vortex. If you've managed to escape them both, then you may live in California, where the only thing you need to deal with is the worst drought ever, and the threat it could last another 200 years. Equally terrifying, the Big One is still coming any day now. Then there's that giant asteroid headed our way.

It's amazing (we've survived) out there.

Pointing fingers everywhere but inward

From our perspective, no one entity is entirely to blame, yet it seems many within the enterprise keep looking to find someone to carry that torch.

Most recently (or, every spring) it's chasers taking the heat. They are unethical disastermongers feeding an "unwilling" media tornado imagery.

Like most blanket statements, reality is often much less easy to define and label. In addition to some bad apples, chasers are also researchers (<a href="http://www.vortex2.org/home/'>a lot of researchers, really), students, photographers, and plenty of everyday folks who just want to see nature at its most awesome. Trust us, a supercell with unimpeded views is awesome.

Related: Spotter Re-school: Reporting Crucial Severe Weather Updates vs Getting Crucial RTs

Last winter it was those tech savvy teenagers on Facebook. Darn them, darn their algorithm-understanding-and-cheating minds! Granted, they did cook up a pretend snowstorm or two.

The roots of the Facebook snowstorms were also laid by meteorologists. Whether right or wrong, the discussion of day 10 fantasy storms has been ongoing for a long time, it's only just now starting to reach the masses on a regular basis. Odds for instantaneous virality are much greater now, and rumors once relegated to a corner full of nerds can go mainstream in a matter of minutes or hours.

We could go on listing others who have been blamed in the free-for-all of weather, but if one stands back and observes -- in between screaming into the void -- it can be seen that huge parts of the enterprise are putting self interest ahead of science, daily. In our every-second news world half(or less)-truths flourish, and in many cases they are quickly lost in the next cycle that's sometimes just hours away.

There seem to be no consequences to fudging or embellishing or otherwise abusing information, so why not? To start: 1) It's a flawed way of thinking, as over time falsehoods gain traction, leading to impaired judgment at best and inaction during crisis at worst. 2) It's relatively easy to combat misinformation and still get lots of interest without unnecessary hype. People want to buy weather even without the sales pitch.

Avoid adding to confusion for the sake of shares

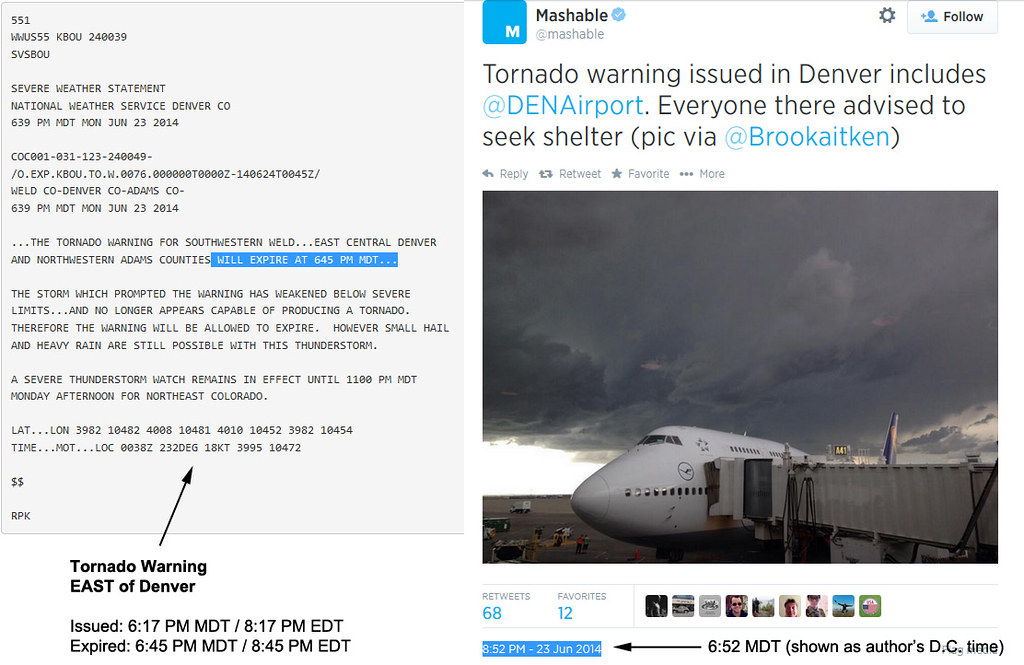

While overall weather is big business, tornadoes are like diamonds. Put one in (or, in the above case NEAR) a big city, add in an airport and it's irresistible tweet material. Never mind the tornado warning expired about 10 minutes prior to the tweet, with no reports of tornadoes from any of the thousands of people in the area who would have had eyes on it.

The Denver International Airport Twitter account was one of the first to respond. No tornado, no reports of tornadoes, back to normal operations. Better warned late by an account you don't expect to be warned by than never?

While we're here, let's get this out of the way: unless you're the NWS and living by an old set of rules that are slow to change there's no real reason to type in ALL CAPS.

In #SD RT @tychistormTVN: EMERGENCY RESPONDERS NEEDED!! On NE side of WESSINGTON SPRINGS!!! Several people trapped in rubble!!

— TWC Breaking (@TWCBreaking) June 19, 2014Tweets like the one above do not serve much more than making the hair rise on skin of folks who see it roll by.

In the off chance it did actually get someone close by to respond, it may indeed be problematic. In general after a disaster, local response asks for all unauthorized/unconnected people to stay away. This is to allow their operation to be carried out at its quickest and most efficient, but also because people who are not trained to respond often end up becoming victims themselves.

There are undoubtedly a number of ways to re-word such a tweet, even if it's questionable the information is needed on a national stage anyway. Weather is dramatic enough without the added drama.

Know your sources and try to verify

Let's be honest. We are all racing to be the first (or second, or 73rd) to share that WOW photo or video we just came across. Last Tuesday (June 24), a tornado was reported to the southwest of Indianapolis, IN as well as verified using dual pol doppler radar.

A few maybe tornado pictures were posted and quickly scooped up by the usual unquestioning sources. Then a big beautiful tornado hit the wire:

We'll leave names out of it here, but let's just say there were way too many well-known media company representatives looking to get usage rights. The tornado was from 1957. A few simple clicks could have told that story to anyone interested. Yeah, it was retweeted plenty too before being outed.

Related: Snuffing out social media's fake weather photos

Among the more famous examples of being trolled by a "source" may be the Sandy tweet about the NYSE flooding. It was picked up by the National Weather Service, <a href="http://www.imediaethics.org/News/3550/Cnn_corrects_new_york_stock_exchange_flooded_by_sandy_report_wsj_corrects_subway_report.php'>CNN, and The Weather Channel before anyone bothered to ask if it was fact. It was later revealed that it was just a hoax.

"3 ft of water on floor of the NY Stock Exchange" via @TWCBryan #SuperStorm #Sandy #NYSE

— The Weather Channel (@weatherchannel) October 30, 2012In most or all cases some additional "snooping" can bring you the answers you might be seeking regarding authenticity. Even in the fog of weather war.

Few can meet the guidelines of a place like the Associated Press, but everyone using the internet can look for corroborating evidence. Things like. . . Pictures from multiple people and multiple places; Reports from trusted individuals. Questions like... "Does the scene match what would be expected?" Common sense, too. Weather can be crazy, but we can bring it down to earth.

It's not all a game to see whose weather is the viralist

Treating weather as pure entertainment or a game to "win" (chasers reporting rear flank downdraft dust swirls as multi-vortex tornadoes as one example) is a sure way to devolve a science. Coming off peak season, let's briefly look at the fast and loose when it comes to tornadoes.

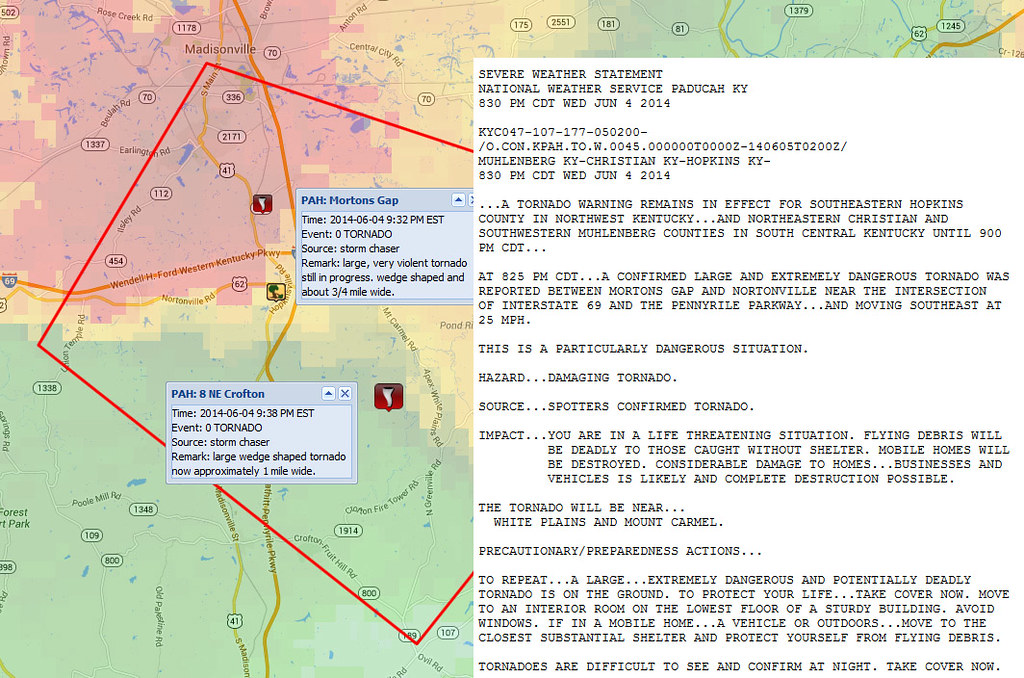

Last nights "wedge tornado" reports in KY were actually a mis-identified macrobrust. http://t.co/Y3U0svN2SK

— Brad Panovich (@wxbrad) June 6, 2014A wedge tornado or wind? Ok, a misreport. The problem is, by this point it was becoming something of an epidemic. With much of the year featuring chasers catching "maybe-nadoes," increasing instances of false reports or stretched information surfaced throughout much of this spring.

Chasers and locals have certainly been calling in reports of tornadoes using words popularized on television with increased frequency, only for no imagery or confirmation of said tornadoes to ever surface. You can't necessarily blame them with the proliferation of "possible tornado" pictures shared on social, many of which are scud or other misidentified features.

Worst yet, some of this has made it into official warnings. It's almost becoming "pics or it didn't happen" since there's now nary a daytime tornado that touches down without evidence.

Above we dig into the example of a bad chaser report helping trigger a "Particularly Dangerous Situation" warning. It's dire, and totally wrong.

In the end, the event was indeed a long-lived macroburst, as perhaps should have been ascertained by the storm velocities and lack of a debris ball -- but we digress.

Sans chatting with the chaser it's hard to understand if this may have been a product of the competitive spirit in the "sport" these days, or a pure error of not knowing a big rain shaft wasn't actually a violent tornado.

At the very least, reports should aim to do no harm. Fake tornadoes don't earn a notch on the belt. Heavy-worded warnings that do not even verify as a tornado are obviously good for no one.

Thinking ahead

We all need to consider what might happen online and what it might cause offline when the next Katrina comes.

Rumors already run rampant, and the race to report first is often more important than reporting at its finest. One thing when the skies are sunny, another in potential or actual disaster situations. That's a time to unabashedly turn the sell off, and probably become less emotional (think TV anchors in the heat of it).

In any emergency situation it is imperative that you put the public interest ahead of the organization's interest. Your first responsibility is to the safety and well being of the people involved. --Clark Communications

Show good taste. Avoid pandering to lurid curiosity. --Society of Professional Journalists

Possessing a strong voice is more important than possessing a loud voice. Being on your audience's team rather than trying to play them will ultimately lead to the best result. Any group that trusts its source will tell others and share about it even when not directly asked to.

Part of a "weather ready nation" is understanding the threats that impact us and not being confused by a deafening roar of noise around us. Rather than expending intense energy outmaneuvering the competition during crisis situations, we should seek to supplement one another with information that fits together to tell a bigger story.

We can also better prepare as thought shapers by keeping detailed and fact-based information coming on down days, even if interspersed with the "10 Things We Should Fear May Be Lurking around the Corner." Continuing to educate ourselves in an effort to better understand our multi-faceted passion, and not proliferate misinformation, should also be a top priority for everyone.

There is a great responsibility across the meteorological world to make every effort to do it right, and examples of positives from social media and blogs are numerous. While a subgroup like chasers may argue (to general eye-rolling) that they do what they do to save lives, the fact of the matter is many in the world of meteorology are doing just that both online and off.

With this in mind, one core question is always floating out there: If we dilute each and every event like it's the worst we've ever seen, what happens when one actually is?

We are in this together. Competition is a way of life, but the community can be stronger and more coherent if it is less balkanized. Seek out people you trust in multiple sectors of the field and set examples for the rest.

Let's all take a step back from social-mayhem for just a moment, and remember why we're all in this field to begin with. An undeniable, and seemingly unquenchable passion for the greatest things on earth: weather and nature.