With few exceptions, the 2022 water year was exceptionally dry across the central and southern plains

The numbers for the 2022 water year, the period ranging from October 1, 2021 to September 30th, 2022, are in. For many folks living across the central and southern plains of the United States it was another starkly dry year, with some locations seeing their driest water year on record.

What is a water year?

The term U.S.Geological Survey "water year" in reports that deal with surface-water supply is defined as the 12-month period October 1, for any given year through September 30, of the following year. The water year is designated by the calendar year in which it ends and which includes 9 of the 12 months. Thus, the year ending September 30, 1999 is called the "1999" water year. It differs from the calendar year because much of the precipitation which falls in the autumn and winter across the West will accumulate as snow and won't melt until the following year's snowmelt.

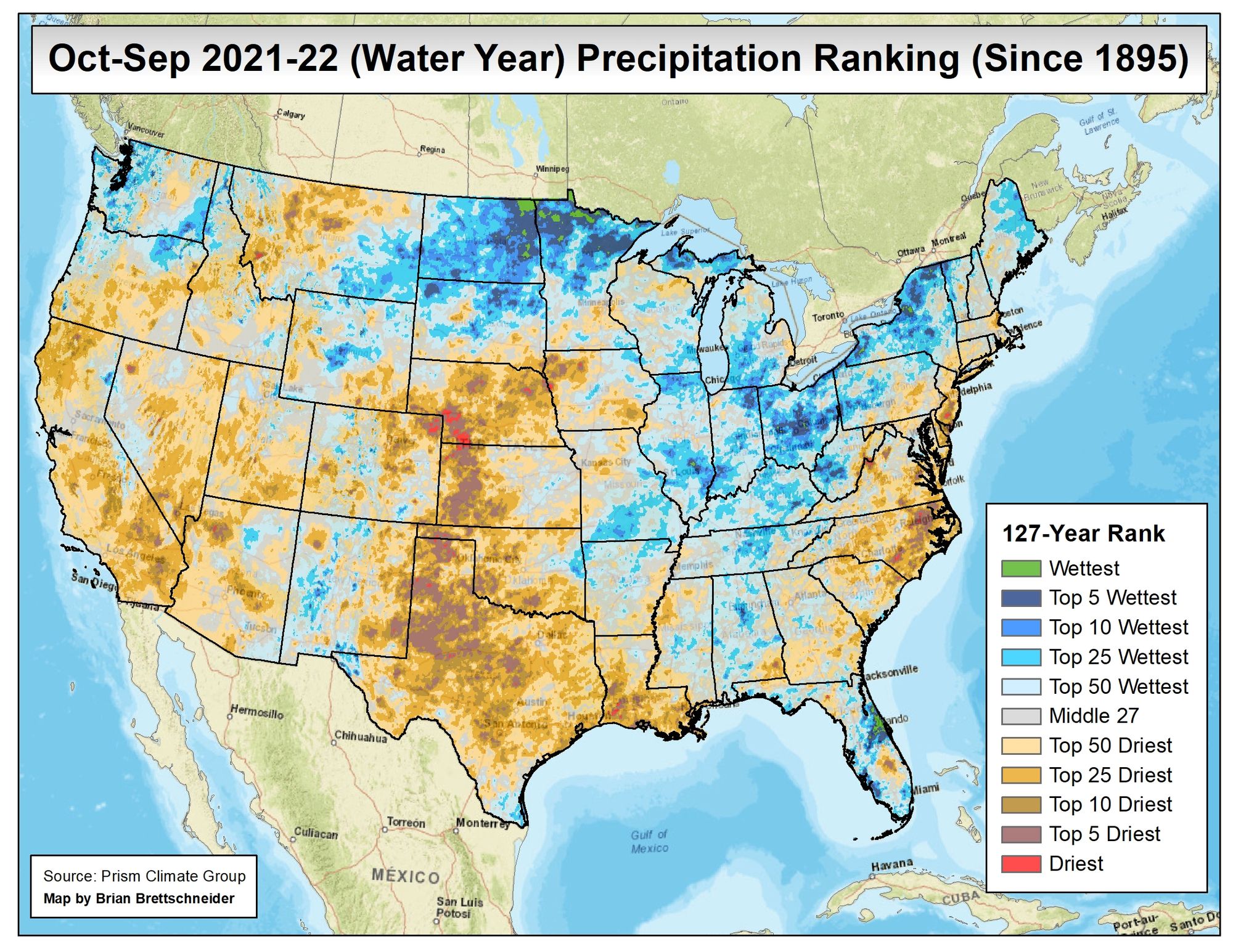

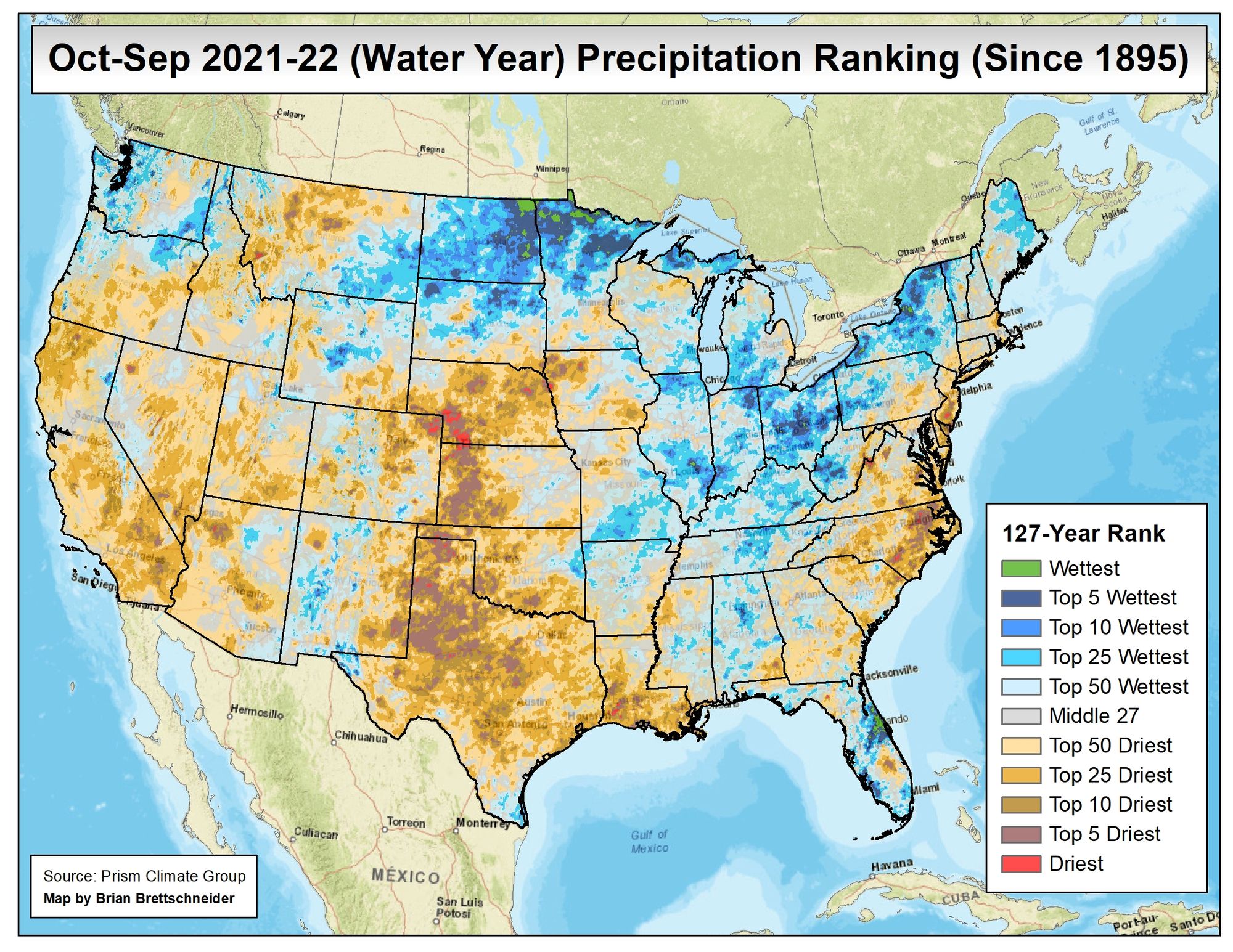

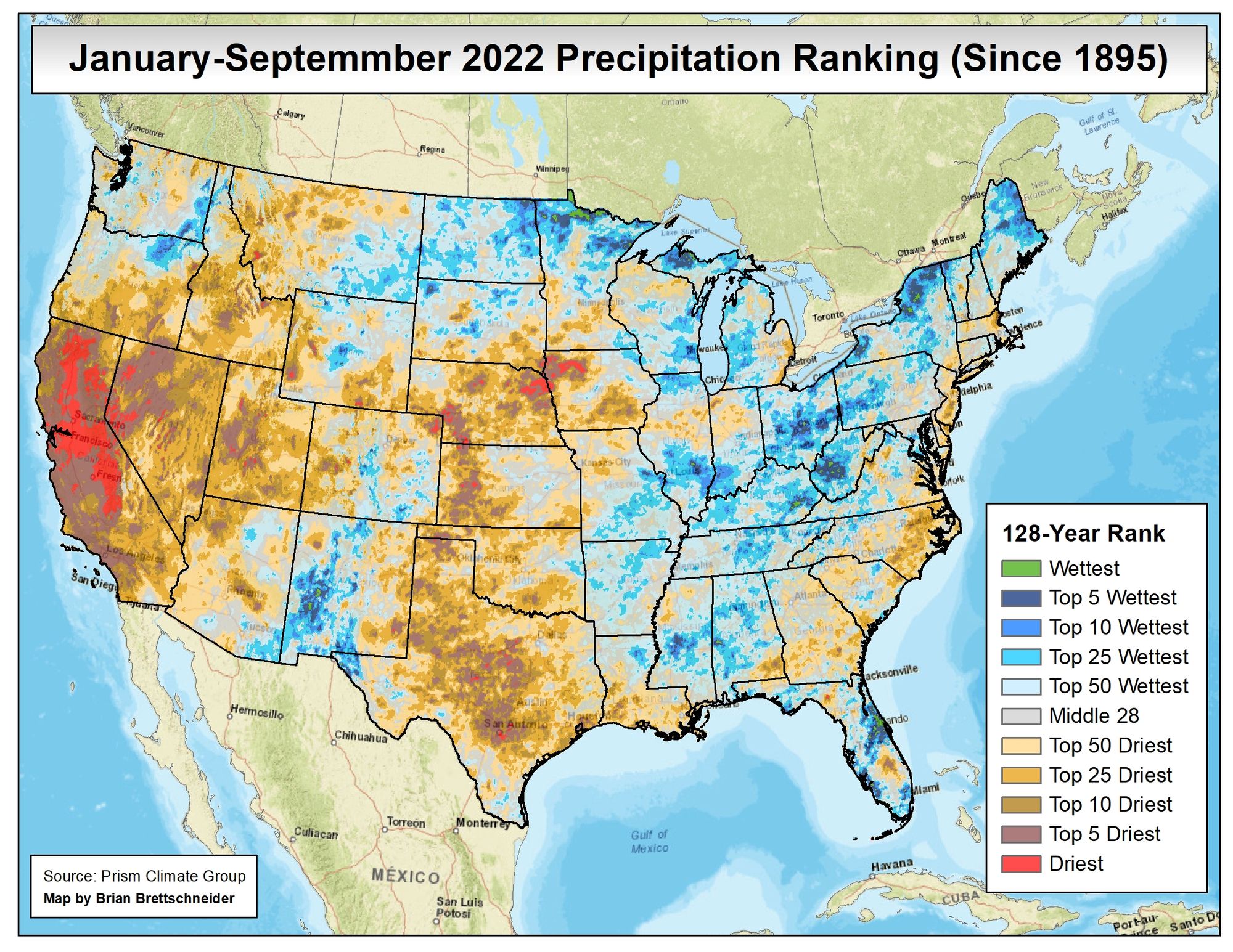

The map below, prepared by climatologist Brian Brettschneider, shows precipitation rankings for the 2022 water year. In it we see a large swath of land from Nebraska south through Texas experienced a top 10 or greater driest water year on record in 2022.

If we look at just the 2022 calendar year through September we see that for Colorado there has been a bit of an uptick in moisture, but most of the greater region, particularly those to the east, have been quite dry year-to-date. California, which had a bit of a boost in snowpack early in the 2022 water year, has been extremely dry thus far in 2022, and continues a record-setting dry streak to kick off the new water year.

If we look at at a few individual weather stations from across the region you'll be hard-pressed to find a station which reported average or above average precipitation for the 2022 water year.

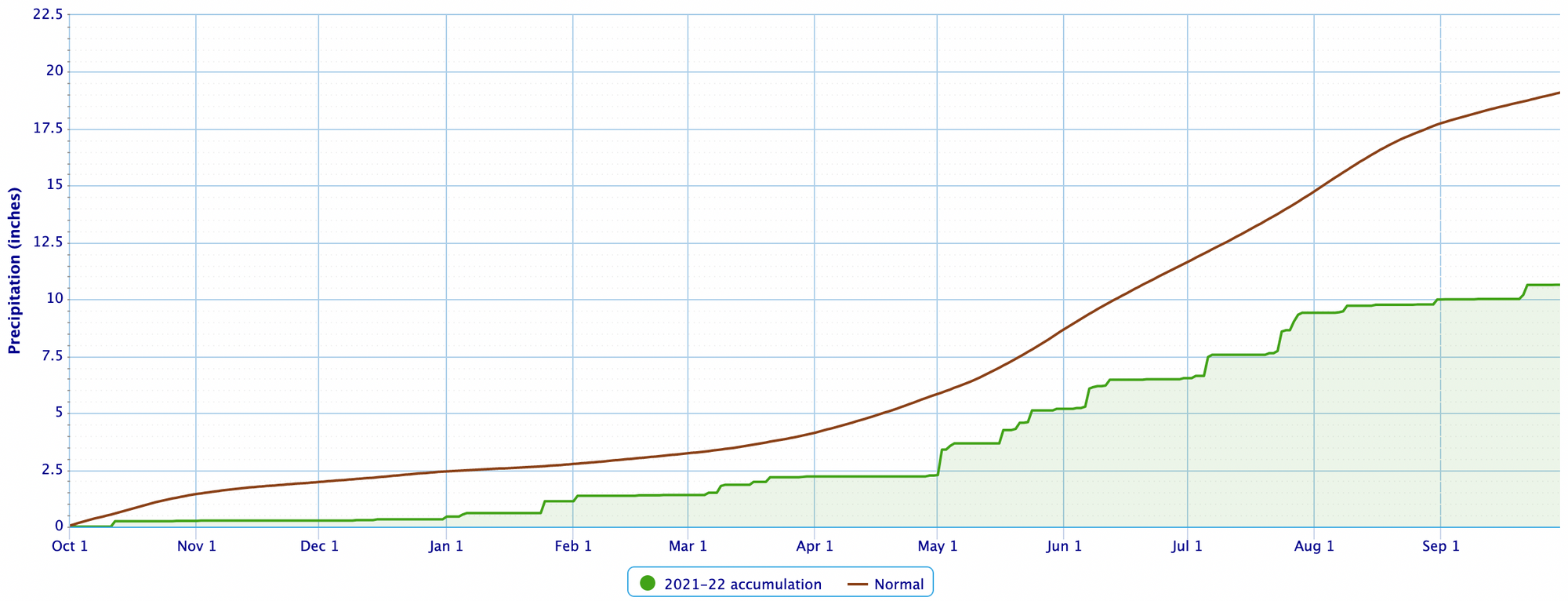

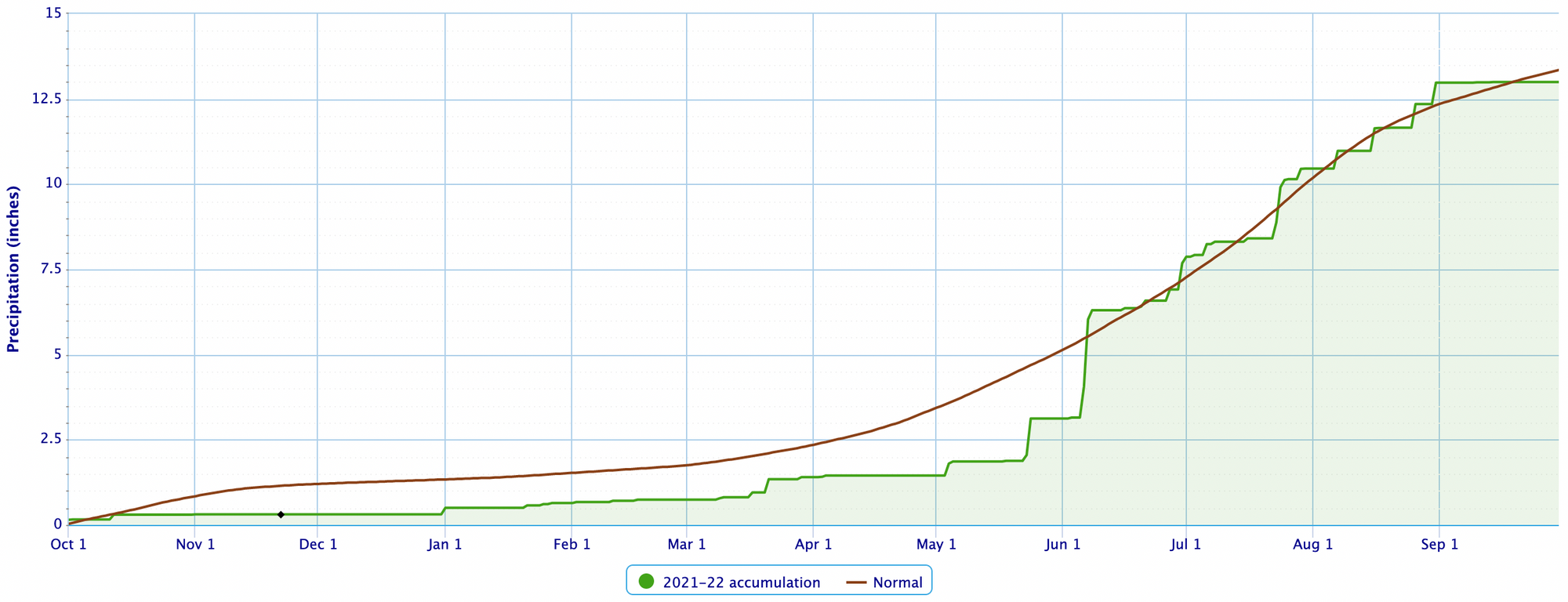

Goodland, Kansas:

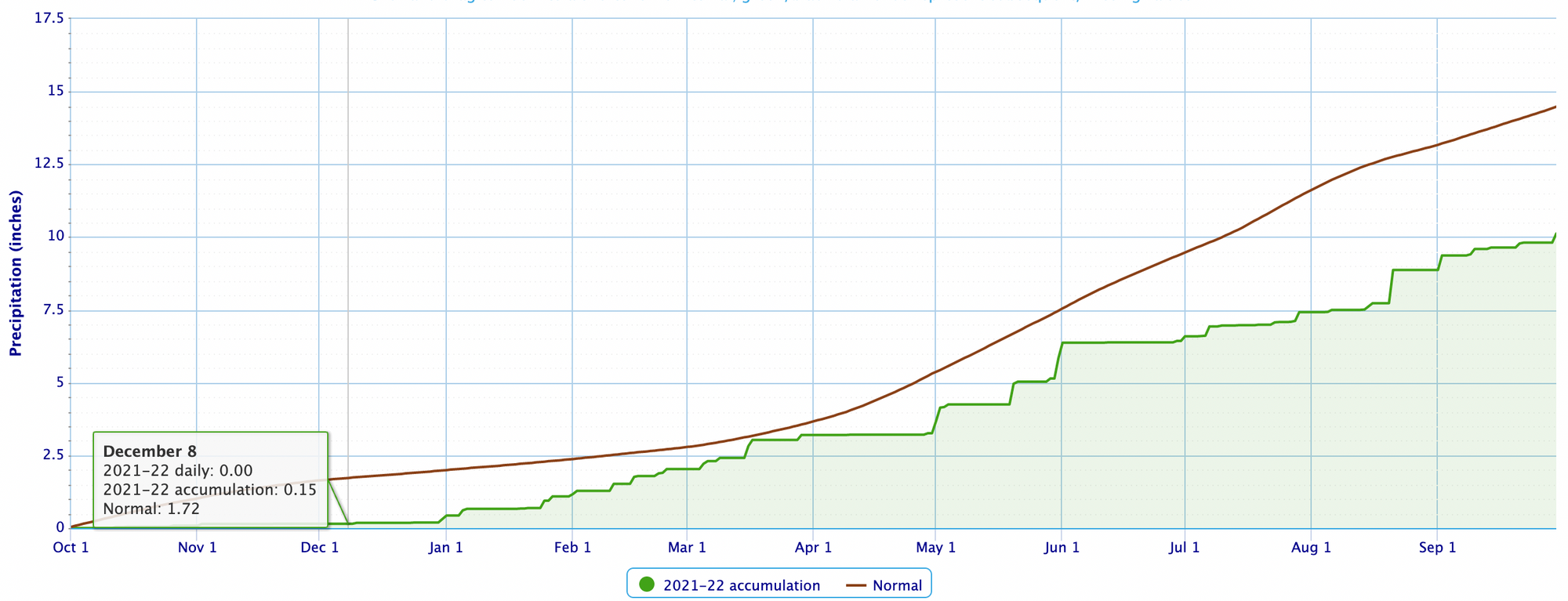

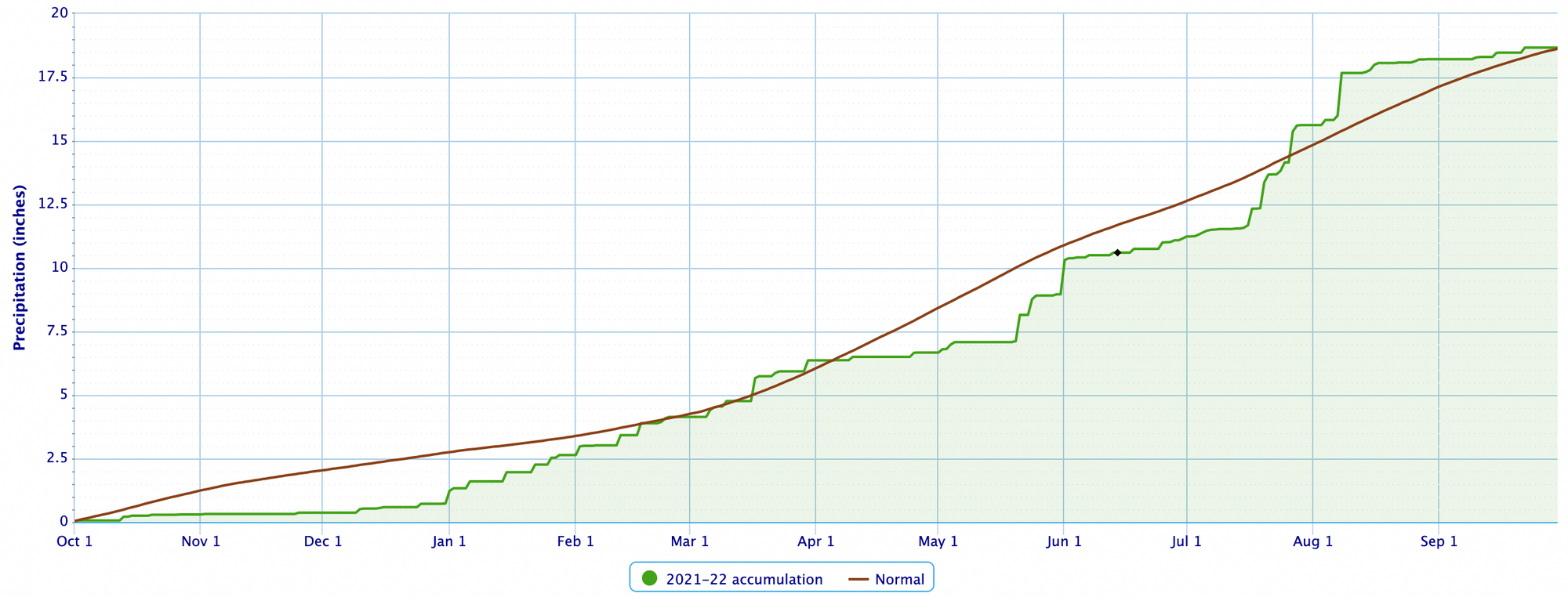

Denver, Colorado:

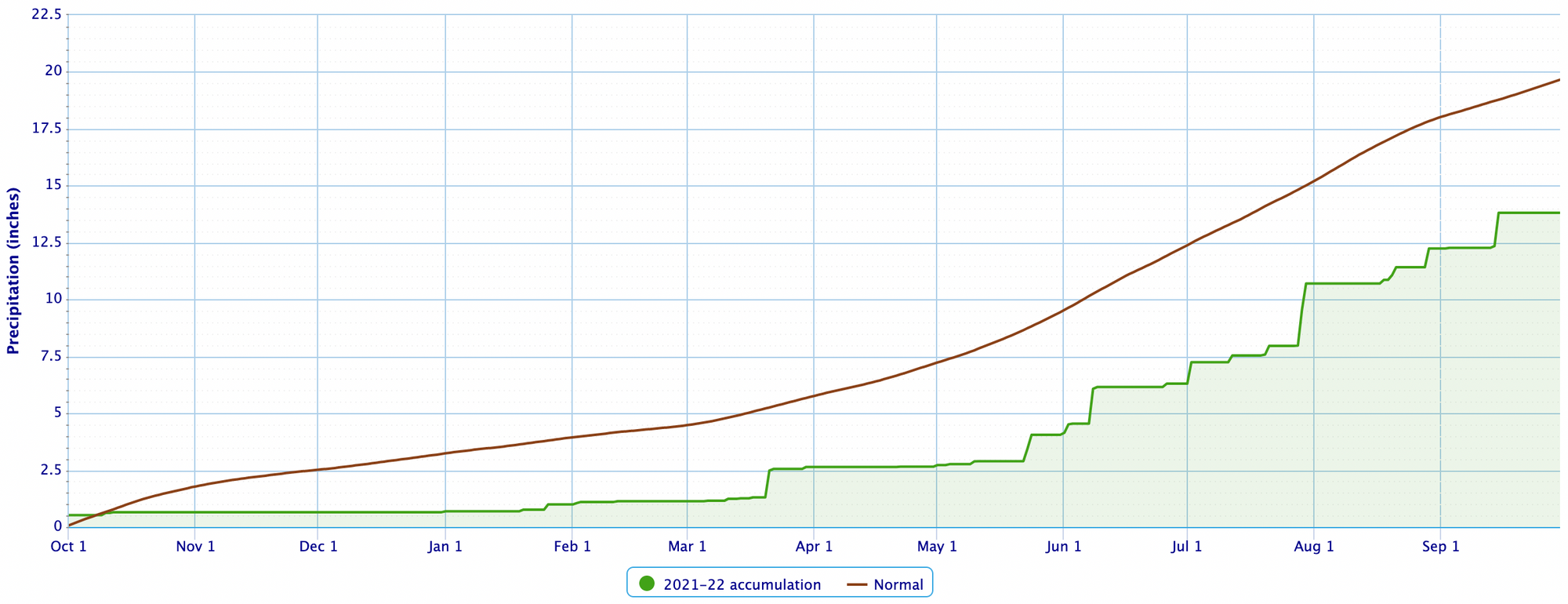

Amarillo, Texas:

One area that managed a near-average 2022 WY was (portions) of southeast Colorado. This was in large part to a fairly active 2022 monsoon, which brought drought relief primarily to Arizona and New Mexico, but some of that moisture made its way into central and southeastern Colorado as well.

In the chart below, note the uptick in precipitation in June, followed by near-average precipitation through the remainder of the summer. Due to the convective nature of the monsoon, not all locations across SE Colorado saw the precipitation bump this summer, but as you can see in the map above it (in general) was a bright spot among a mostly drier than average period for those surrounding.

Lamar, Colorado

The same is also true for a few weather stations in and along the foothills around Denver. While DIA has been quite dry, places like Evergreen actually pieced together an average water year for 2022:

Evergreen, Colorado

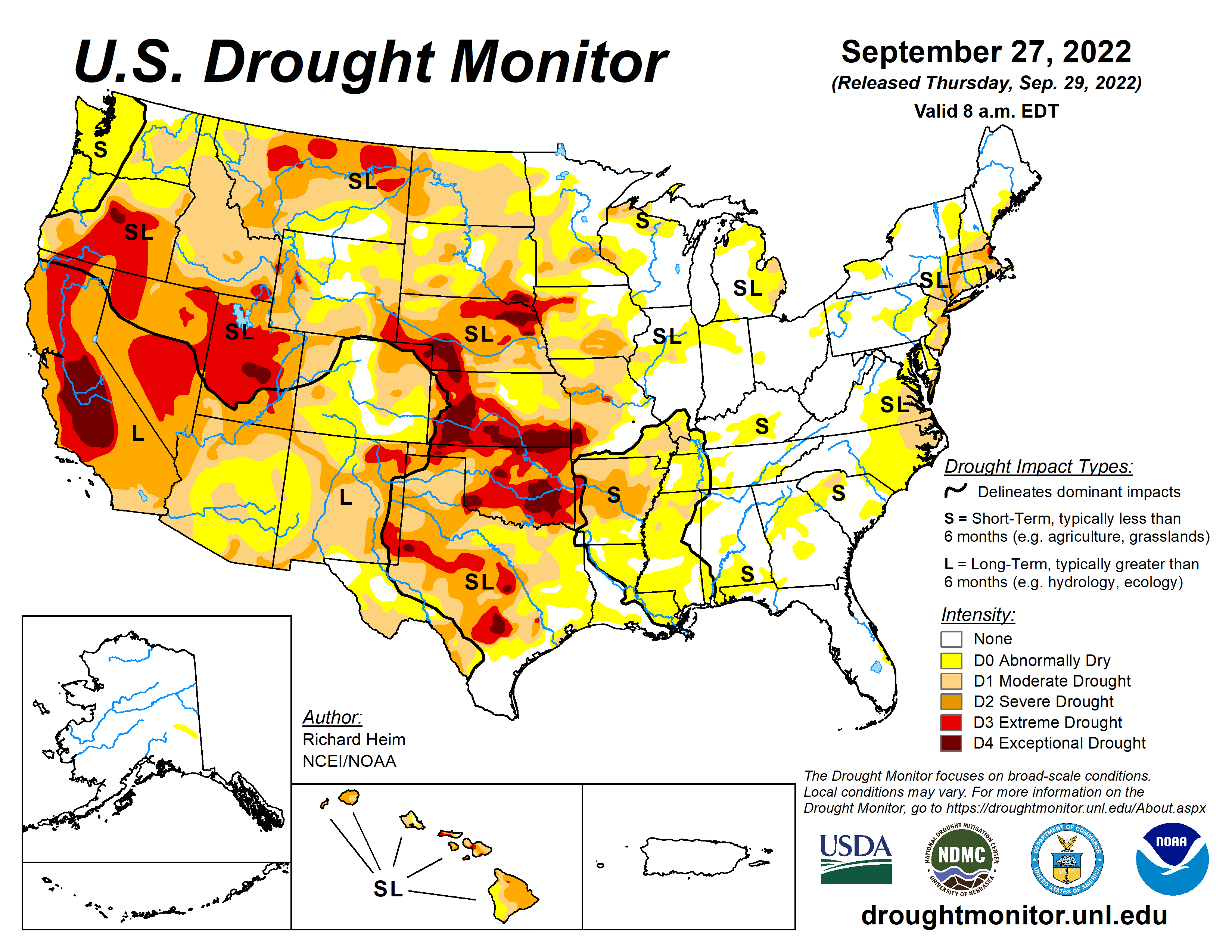

Needless to say, with such great deficits in place over the last year, the drought remains fully entrenched across the Plains states and Western United States as we kick off a new water year.

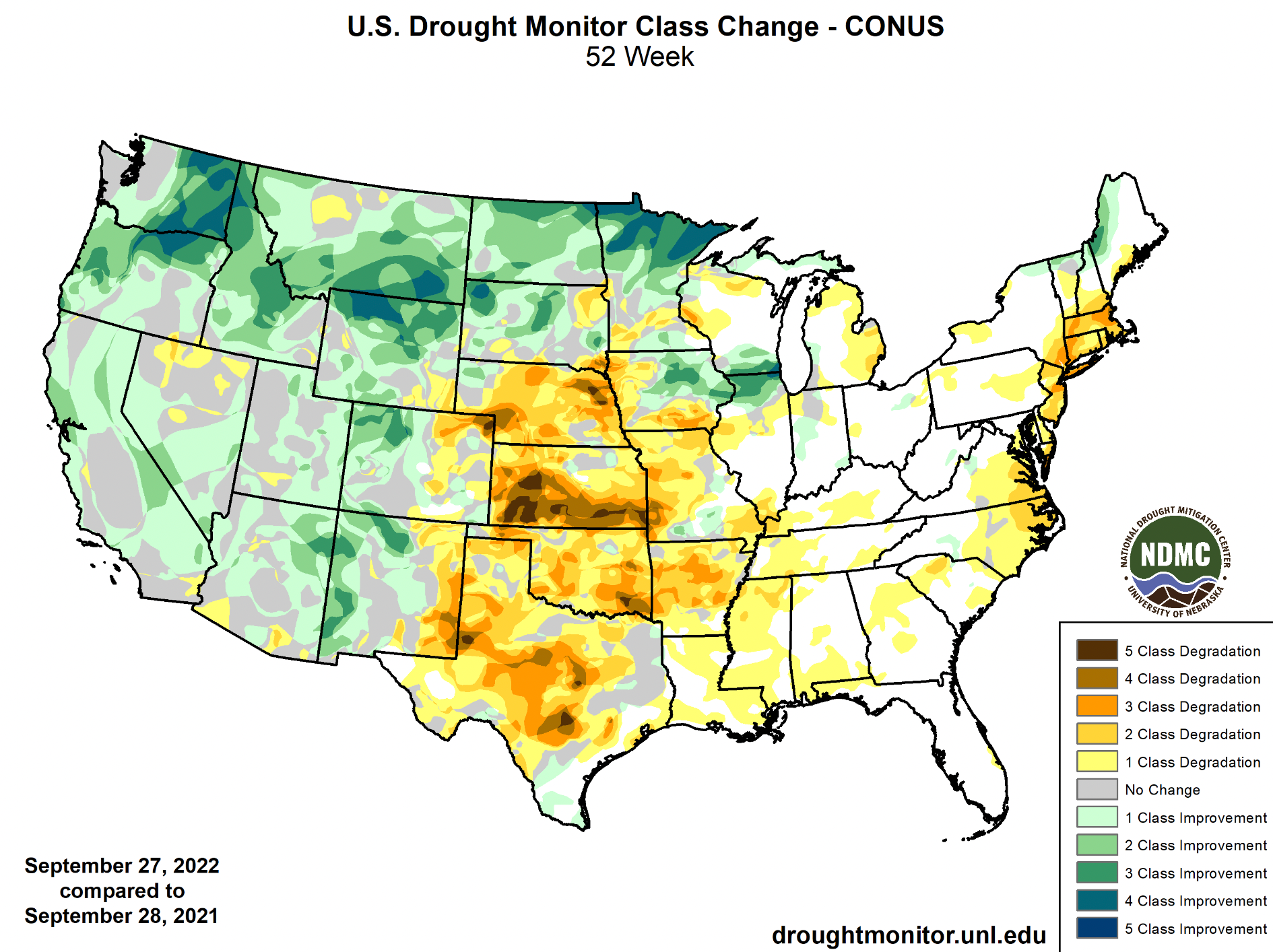

If we look at the Drought Monitor's class change map from the last 12 months, we see some good improvement across the Pacific Northwest and northern tier of the U.S., with even some improvement across California and the Four Corners region despite many areas still running a deficit on the year. For the Plains... no mistaking the tough year it was, with much of the central U.S. seeing remarkable degradation over the last year.

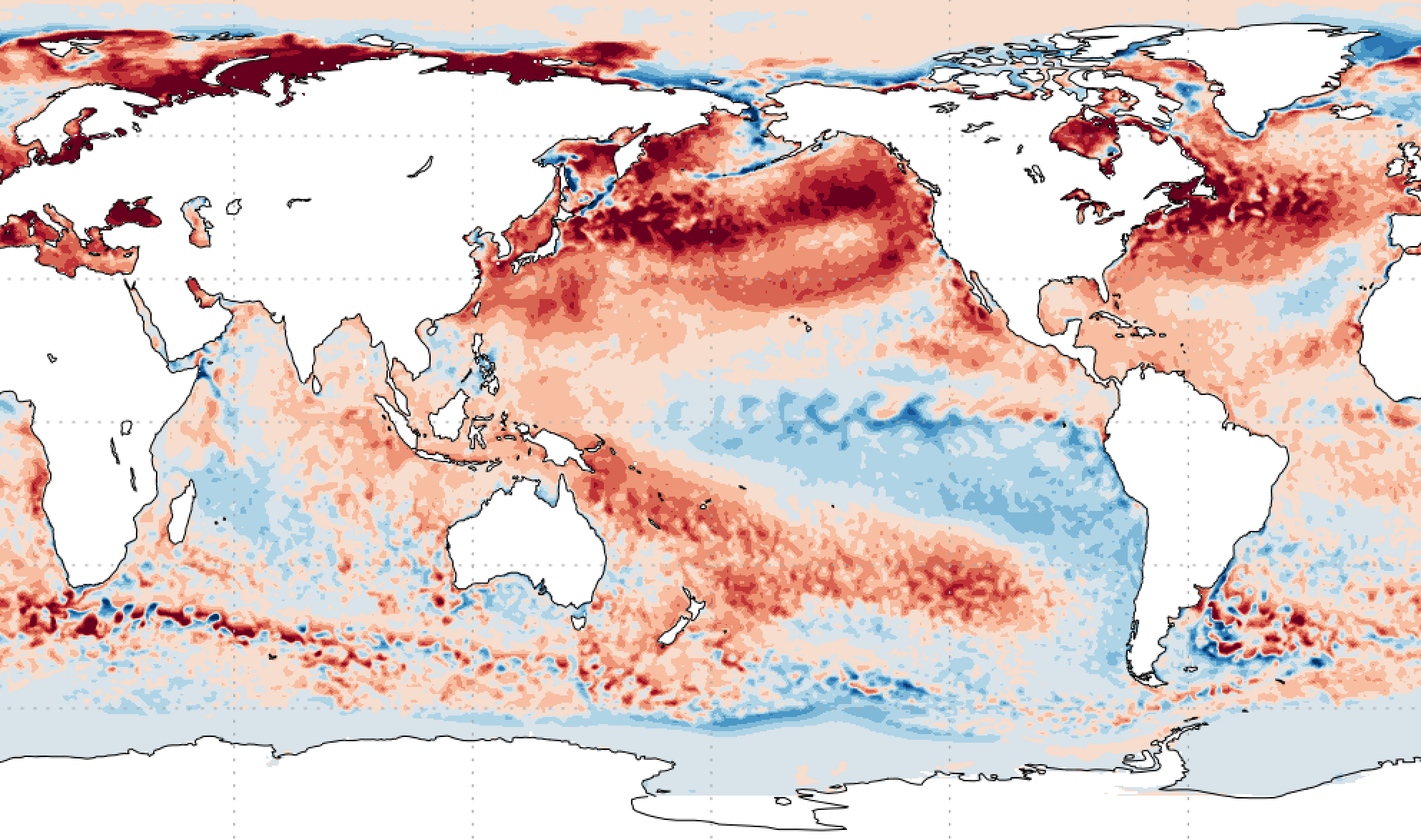

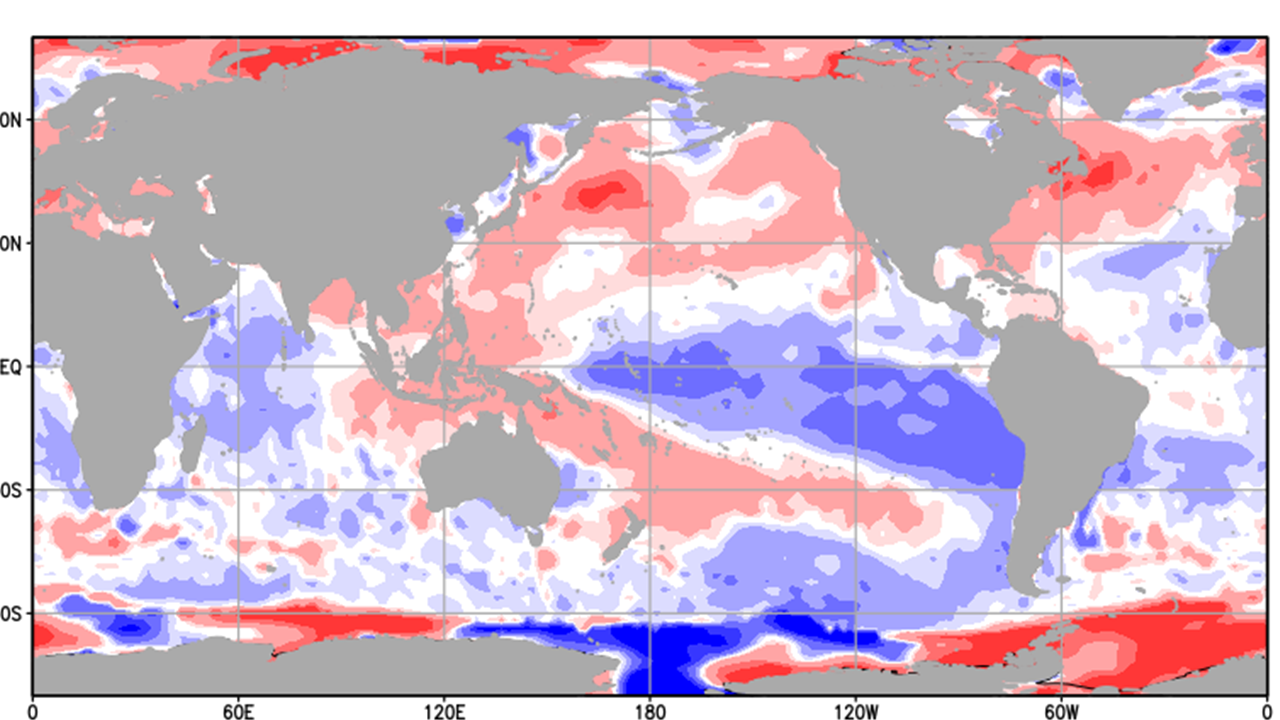

As for what to expect as we kick off the 2023 water year? For many of us it'll be more of the same, at least for awhile. La Niña remains a driving factor in our weather across the CONUS and likely will for the next several months. We've had several updates on the upcoming winter season in recent weeks, and will have another as we head deeper into the month of October as well.

The CPC's winter outlook, issued in mid September, shows a La Niña-esque outlook, keeping the southern CONUS drier and warmer than average, with cooler and wetter than average conditions favoring the northern tier. Details aside, it's hard to argue too much with this idea at this time.