Colorado River: Better Than Hoped For Snow Season Helps Water Supply Outlook

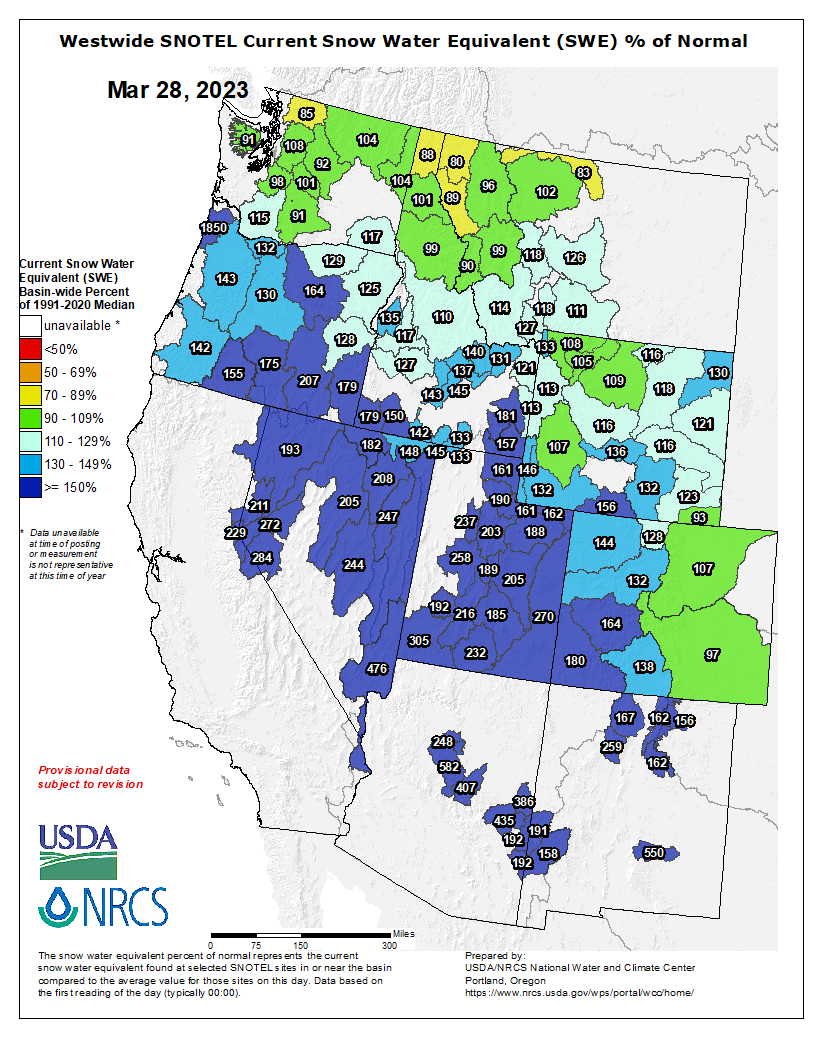

There's a lot of snow in those Rocky Mountains, the Sierras, and the Cascades to help the water situation across the American West, and the snowpack is so much more impressive than we had expected. Let's break it down closer to the river-basin level across the Western U.S.

For a video discussion, here, the written form follows.

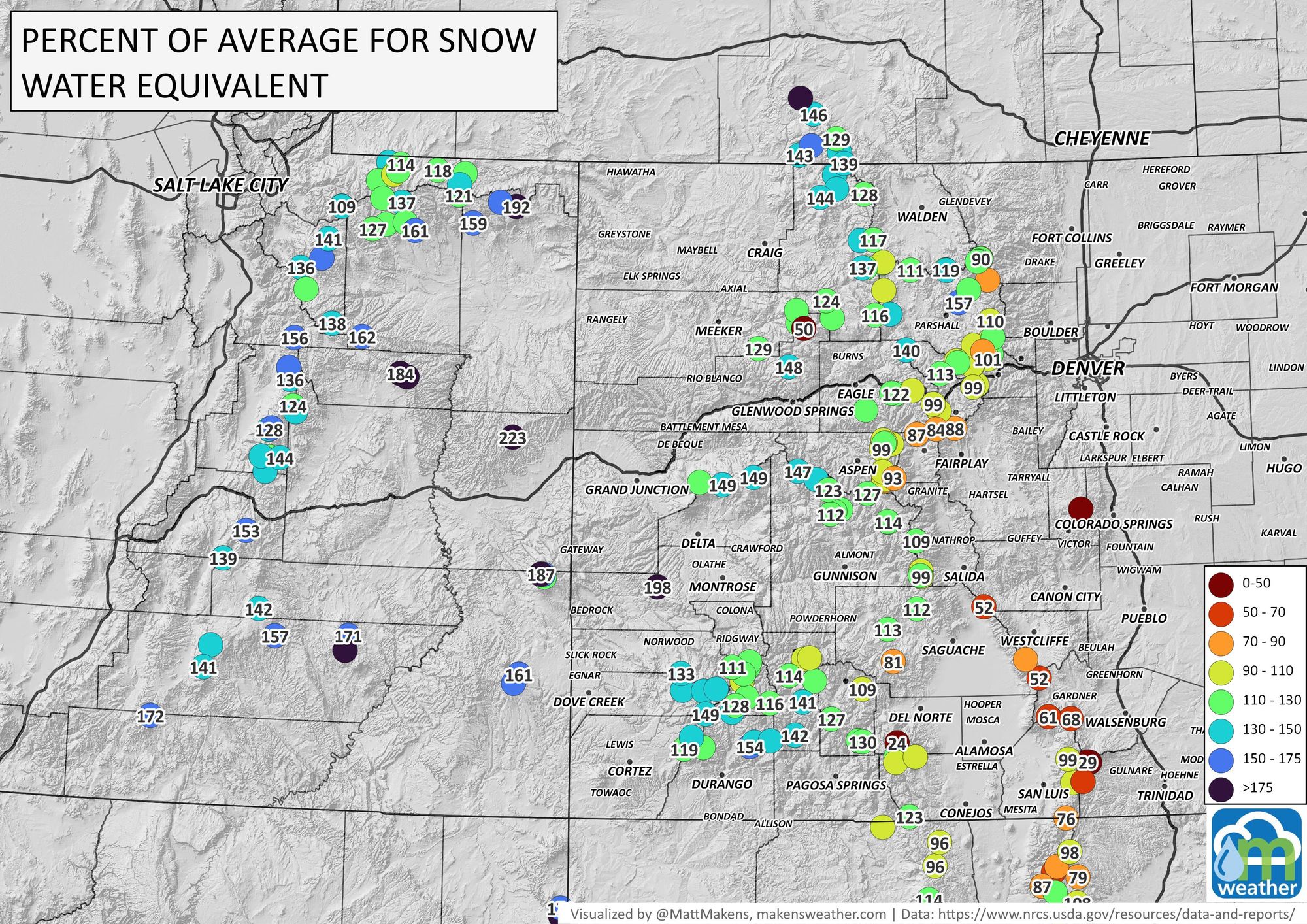

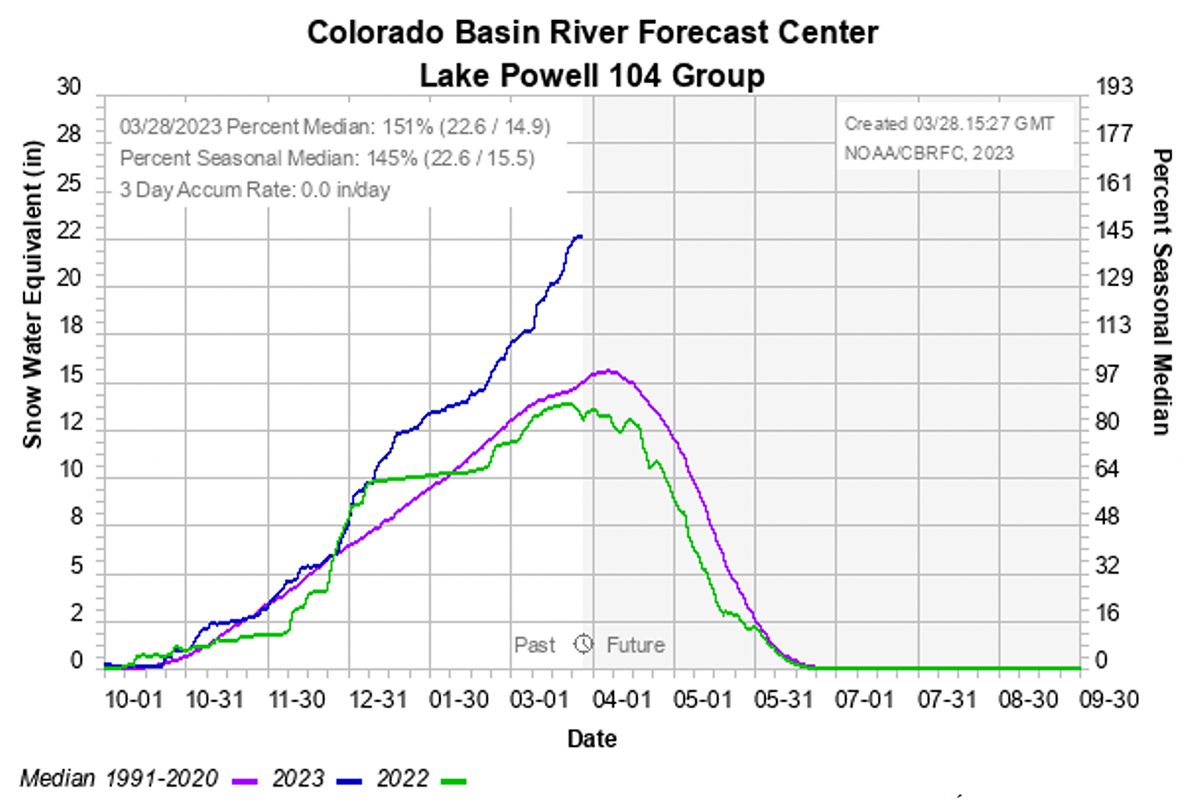

The measurements used here are based on SNOTEL (Snow Telemetry Network) sites that span the West's mountains and serve as in situ data for water resources. So, compiling data from those sites creates estimates for the amount of snow and water from mountain basins that will flow into the rivers and contribute to the more extensive river system.

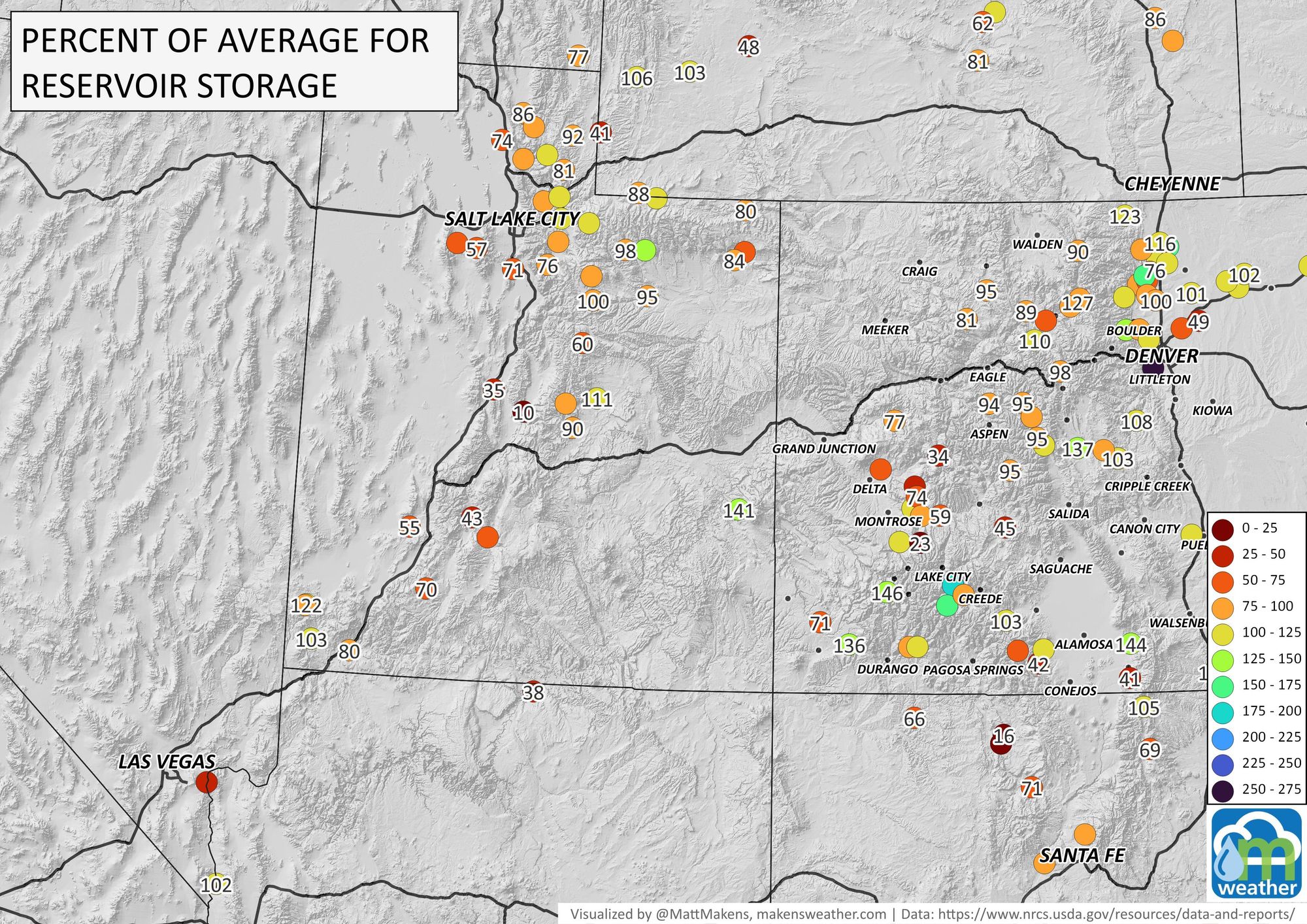

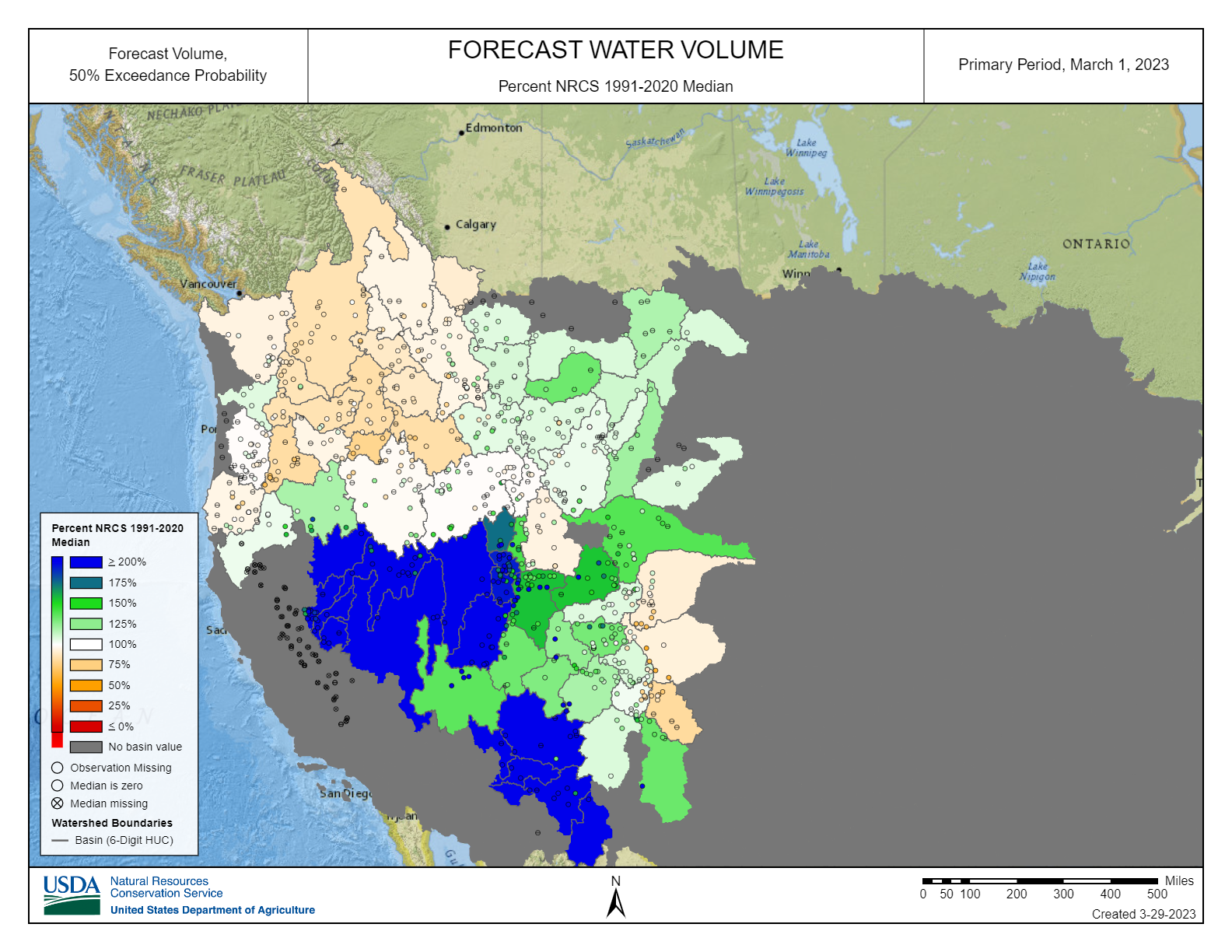

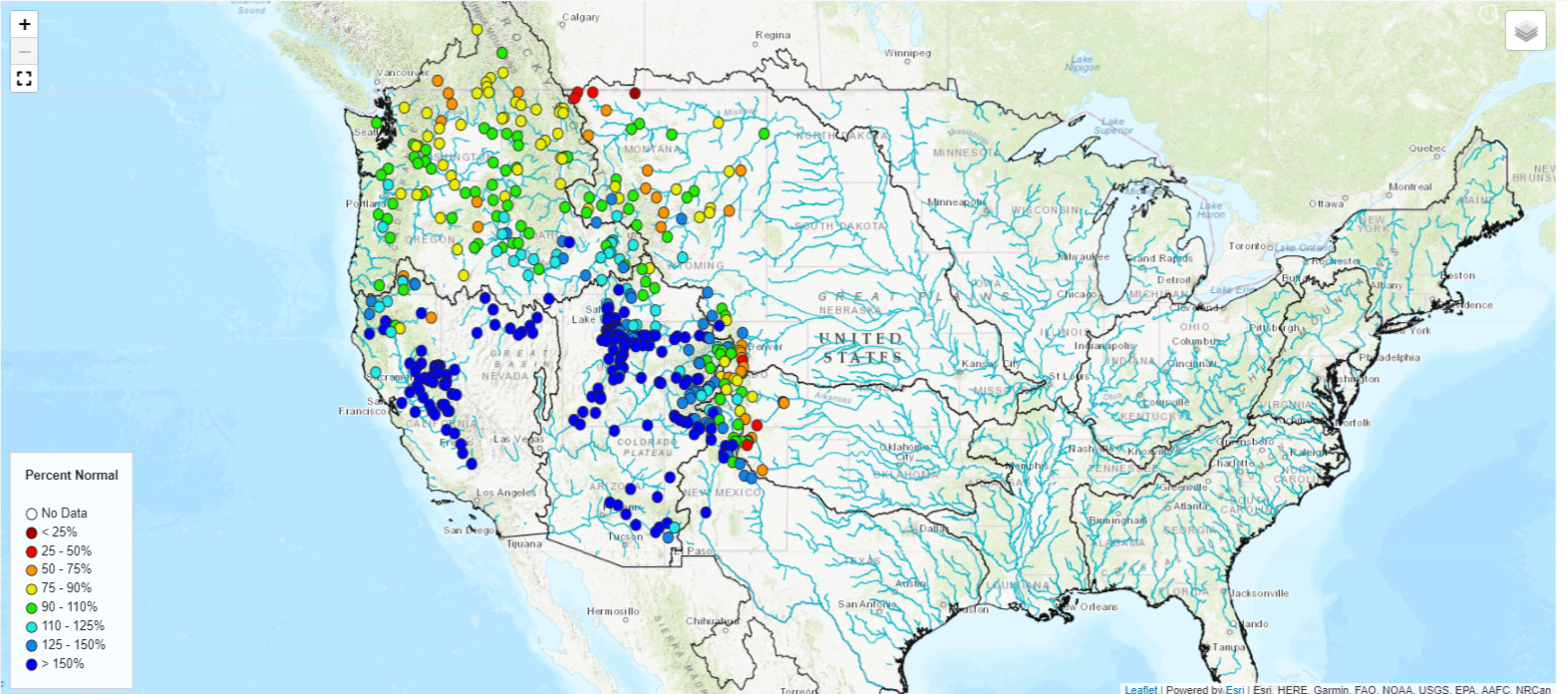

We're looking at all the Western U.S., and many of these basins from Nevada to Southern Oregon, Southern Idaho, down through Utah and Colorado into Arizona and New Mexico, have snow water equivalent 100 to 200 percent normal. When you get way up to the north, we could be doing better, but generally speaking, everyone across the West has a much better water year than expected.

Focusing on the amount of Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) just from the Rockies that will feed into the Colorado River Basin, there's much here to catch your eye. Many of these sites are well over 100 percent of the average SWE; some approach 200 percent, and then some.

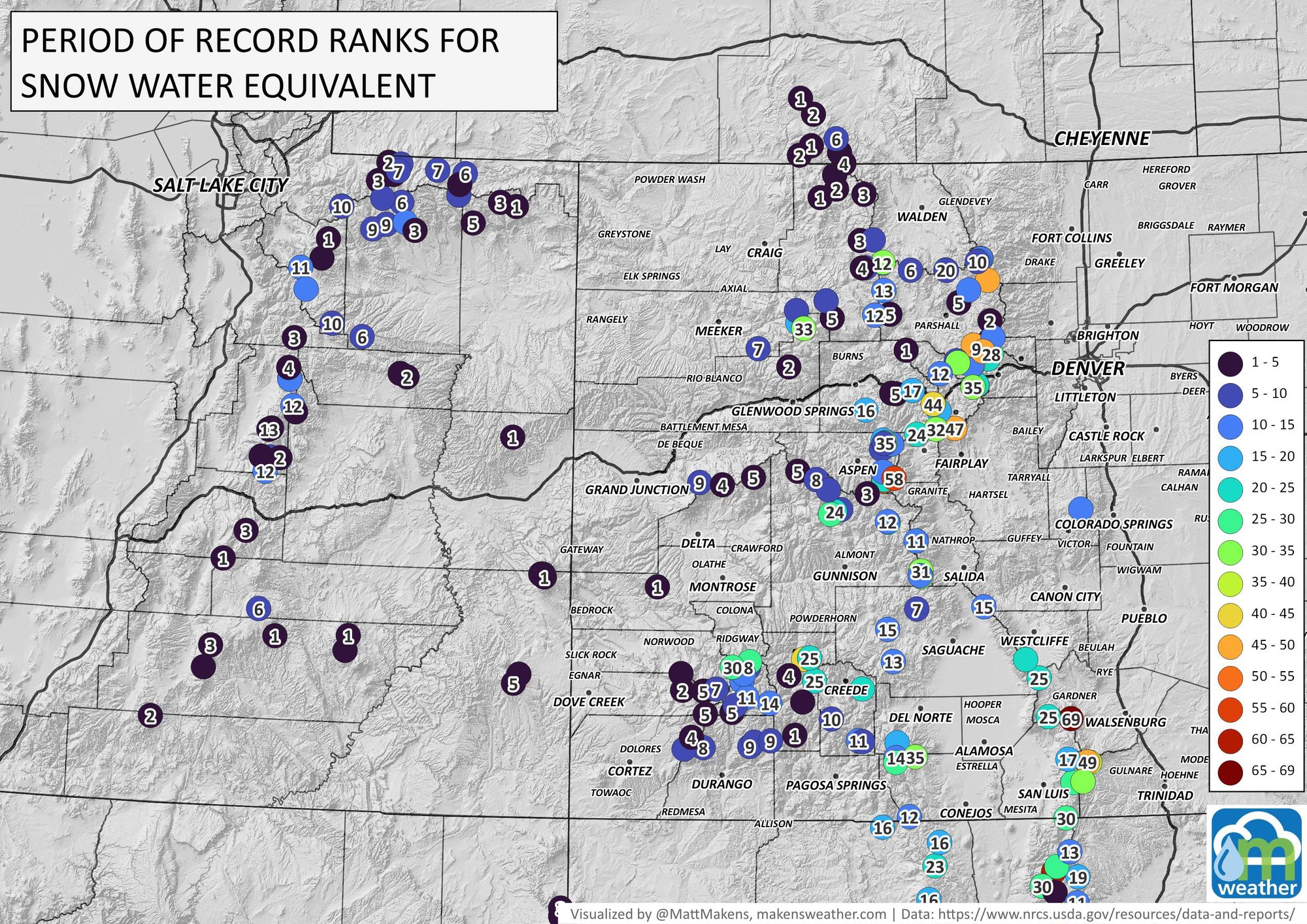

Let's take a look at the same thing but historically. Historically speaking, many sites are within the top five seasons (per each period of record).

Look throughout those mountain ranges; many currently have the highest snow-water equivalent on record.

The snow is excellent for skiers/riders to enjoy before becoming the valuable runoff later this spring and summer; from Steamboat Resort:

As of today, we've surpassed the 400" mark at mid-mountain and the 500" mark at the summit.🥳This is one of the snowiest winters on record at the summit.

— #SteamboatResort (@skisteamboat) March 23, 2023

See you on the mountain this spring!🗻 pic.twitter.com/gbRfDtz8nk

Across the Colorado Basin, it's been a remarkable snow year; most of these locations that will flow into the Colorado are within a 90th to 100th percentile type of season so far. Although, the neighboring Rio Grande and the Arkansas numbers could be stronger.

Focusing on the Colorado River, there's a lot of water upstream that's going to flow into the reservoirs this spring and summer (yes, much will be lost to soil penetration, too, considering soils in these areas aren't very healthy yet. A factor we don't have the expertise to discuss here appropriately).

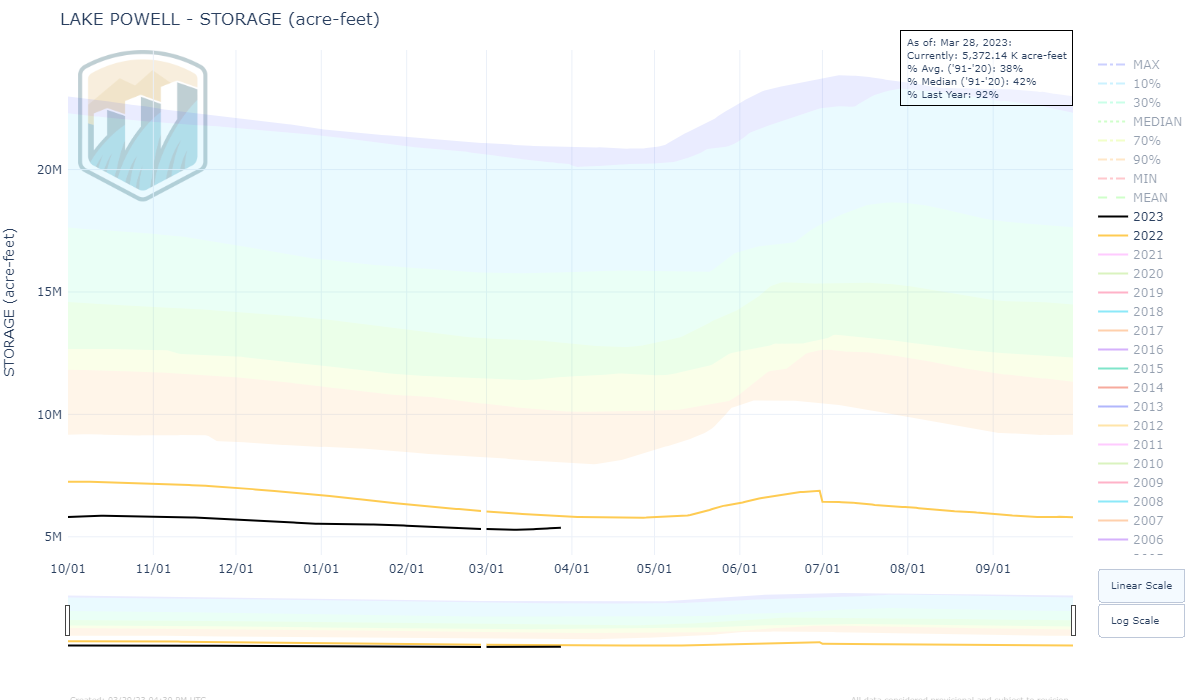

How much of this is going to contribute to Lake Powell? More than last year and what's 'normal,' that's for sure.

That's an excellent graph to see. Yet, a greater perspective reminds us that Lake Powell is desperate for a lot more water than just this one season can provide. Lake Powell's current percent of average storage is only 38 percent, which is lower than last year and historically low.

The takeaway is that we've got such a deficit to overcome; it will take a long time to get back to an average level.

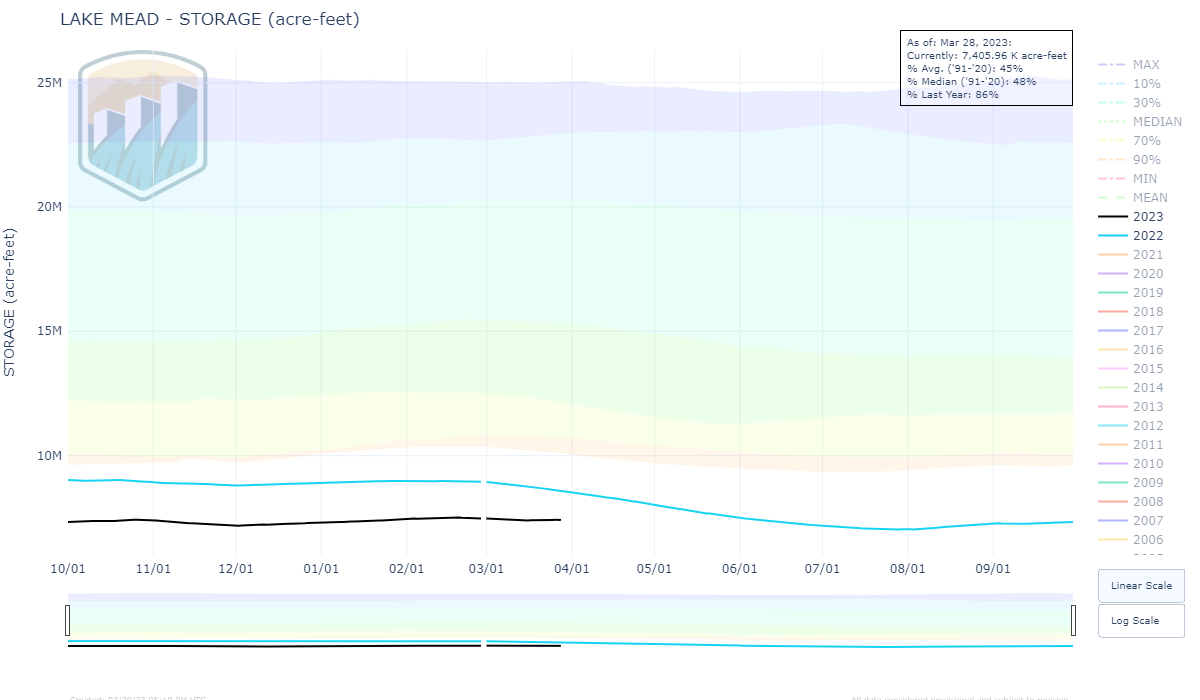

Let's look at Lake Mead, with a situation similar to that of Lake Powell, which is historically low. This year is the black line representing 45 percent of its average storage, and slight fluctuation with all the water so far this year:

We do have upstream reservoirs that are doing much better, like Crystal Reservoir and Morrow Point Reservoir, so there is some headway with the upstream reservoirs that will eventually flow down.

If we go back to how much snow is currently on the ground and how that will contribute to the Colorado River system, the current snowpack will give at least 200 percent of the average streamflow to the system.

As you look over the two images above, the water supply forecasts they represent are less promising for a good runoff year for the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies feeding the Missouri Basin, the Arkansas and Rio Grande contributions will also be poor based on data through today.

For the Colorado, this year is a step in the right direction; We have to be patient while waiting for a full-water system. Remember, things are so low already that it may take four or five, and I've heard some researchers say six or seven years of seasons like this to replenish the Colorado River system fully.

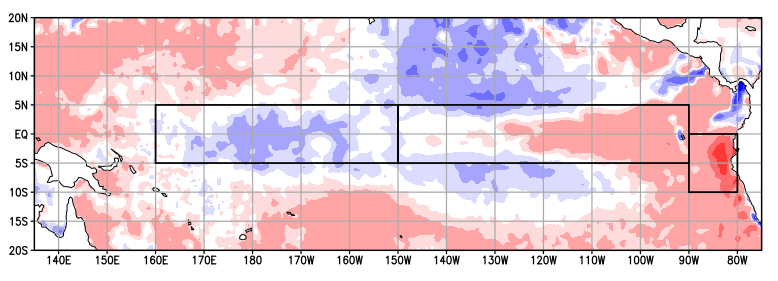

In that light, to add to the progress, the West may get more and more water through the year with the likelihood of El Nino increasing. We discussed this with our paying subscribers weeks ago: