In Hurricane Harvey's Case, a Failure to Comprehend, not Forecast

Anyone paying attention last week knew Harvey was set to unleash the full fury of Mother Nature on Texas. Forecasters predicted this historic event with incredible accuracy, and yet, the most tired story of all ("meteorologists get paid to be wrong") has been written about time and again, starting with a disingenuous comment by the President of the United States last Friday evening – long after officials were briefed, the most extreme rainfall forecasts were issued, and forecasters had accurately predicted a major hurricane at landfall.

Here's the thing: The National Hurricane Center (NHC), and the hundreds of meteorologists across Texas and the United States tasked with forecasting this (dare I say) unprecedented event, did a great job in both forecasting the severity of the storm taking aim at Texas, and communicating the likely hazards that would impact the region for the better part of a week, with devastating effects likely lasting years.

By Tuesday of last week, forecasters at the NHC were already warning that environmental conditions were favorable for development of Harvey as its remnants moved into the Gulf, and that "Interests in northeastern Mexico and along the Texas coast should monitor the progress of this system" as it could produce storm surge, tropical storm or hurricane force winds, "and very heavy rainfall across portions of central and eastern Texas from Friday through the weekend".

On Wednesday, forecasters at the NHC were warning of the potential for "life-threatening flooding" across Texas, Louisiana, and the lower Mississippi Valley, explaining several days of heavy rain would begin Friday and likely continue into this week.

By 4am Thursday morning the NHC began warning of the potential for Harvey to make landfall as a major hurricane:

Data from the Hurricane Hunter plane indicate that maximum sustained

winds have increased to near 65 mph (100 km/h) with higher gusts.

Rapid strengthening is forecast, and Harvey is expected to become a

major hurricane before it reaches the middle Texas coast.

And most importantly, started driving home the potential for incredible rainfall associated with the storm:

RAINFALL: Harvey is expected to produce total rain accumulations of

12 to 20 inches and isolated maximum amounts of 30 inches over the

middle and upper Texas coast through next Wednesday. During the same

time period Harvey is expected to produce total rain accumulations

of 5 to 12 inches in far south Texas and the Texas Hill Country to

central Louisiana, with accumulations of less than 5 inches

extending into other parts of Texas and the lower Mississippi

Valley. Rainfall from Harvey may cause life-threatening flooding.

By Thursday PM, here was the advisory issued by the NHC. No mincing words here.

Graphical Forecasts

Today we are both blessed (and sometimes perhaps cursed) by the amount of data graphics available when a storm is approaching. Whether that's model data now more readily available to the general public than ever before, or graphics put out by local and national forecasters, there are likely more than enough resources today to use to prepare.

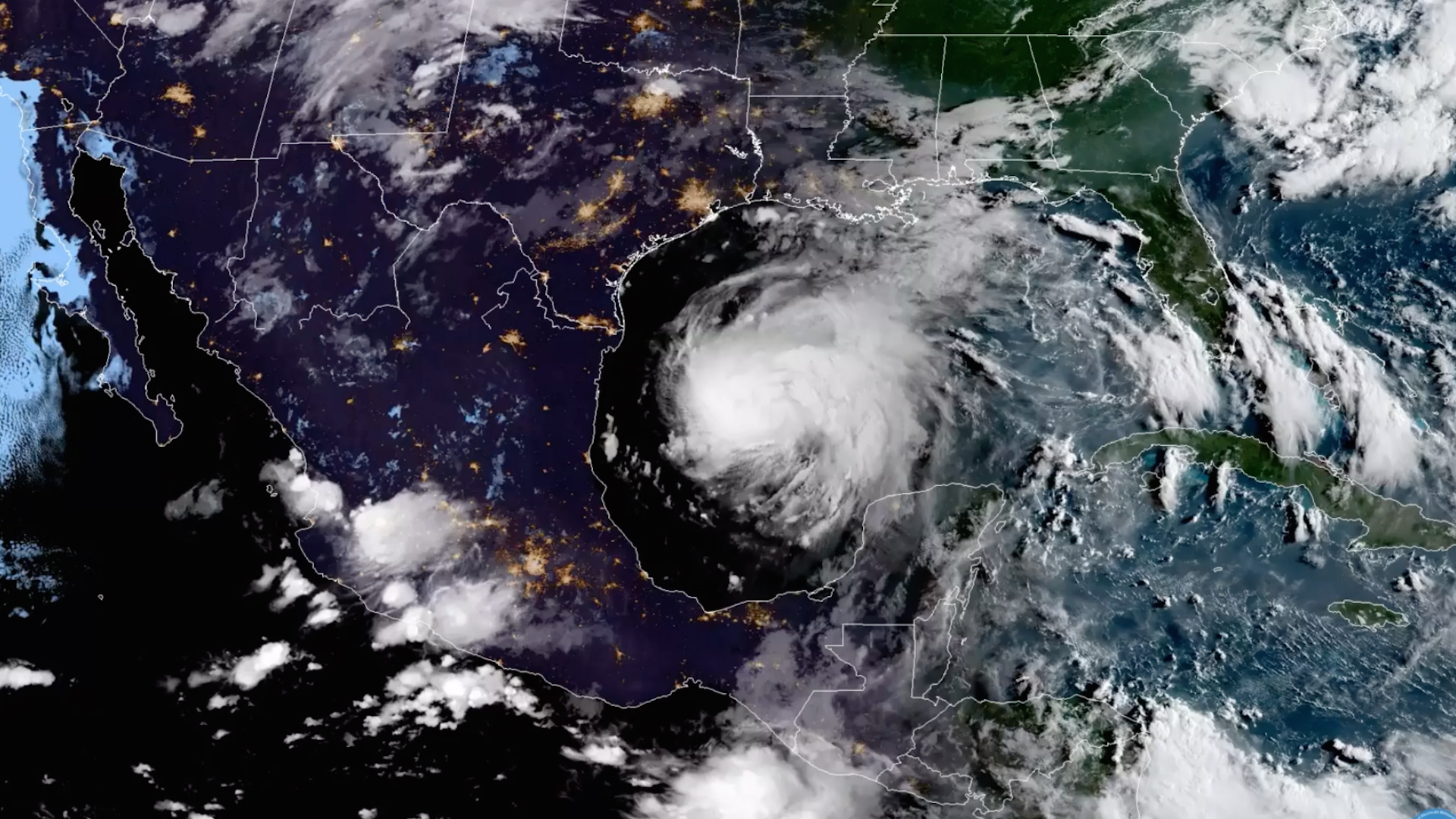

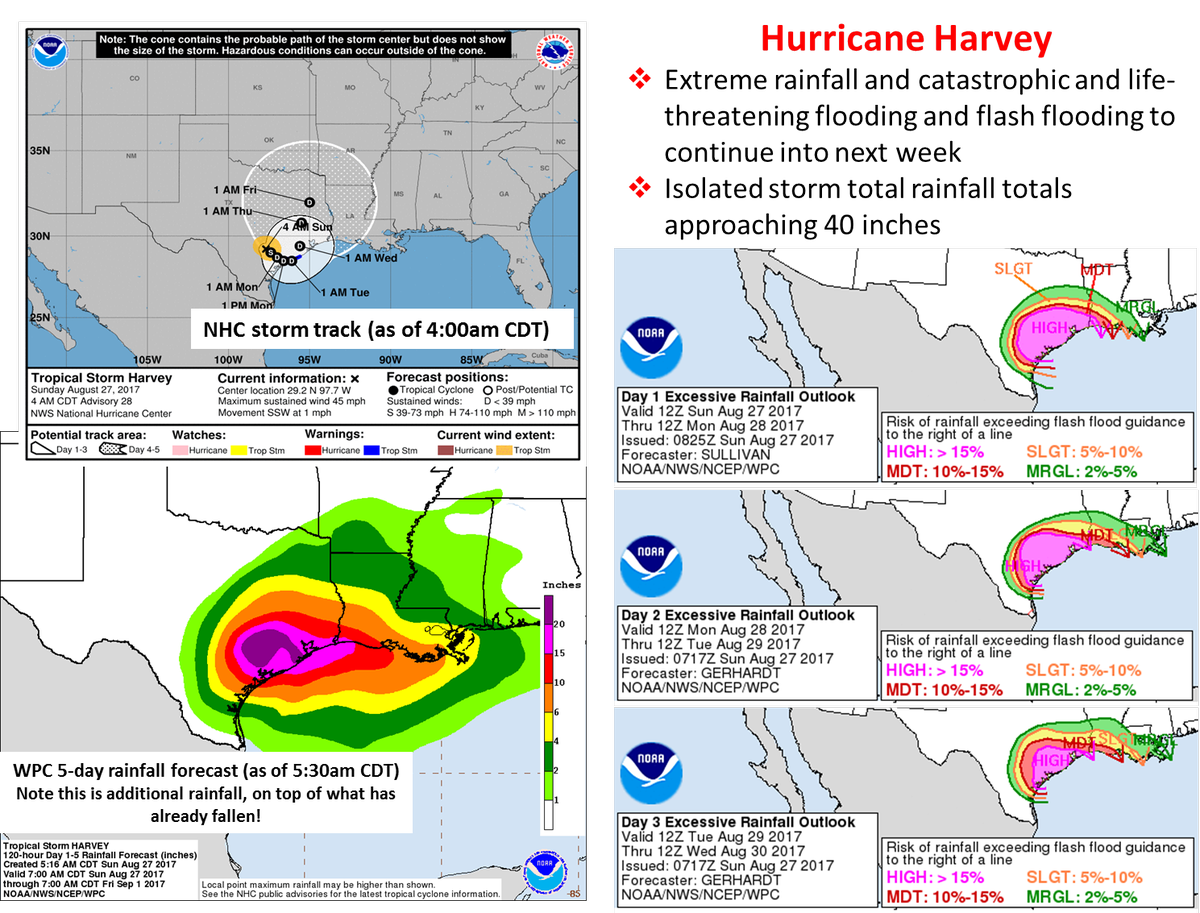

Here's an example of some of the graphics put out by the NHC and WPC for Harvey:

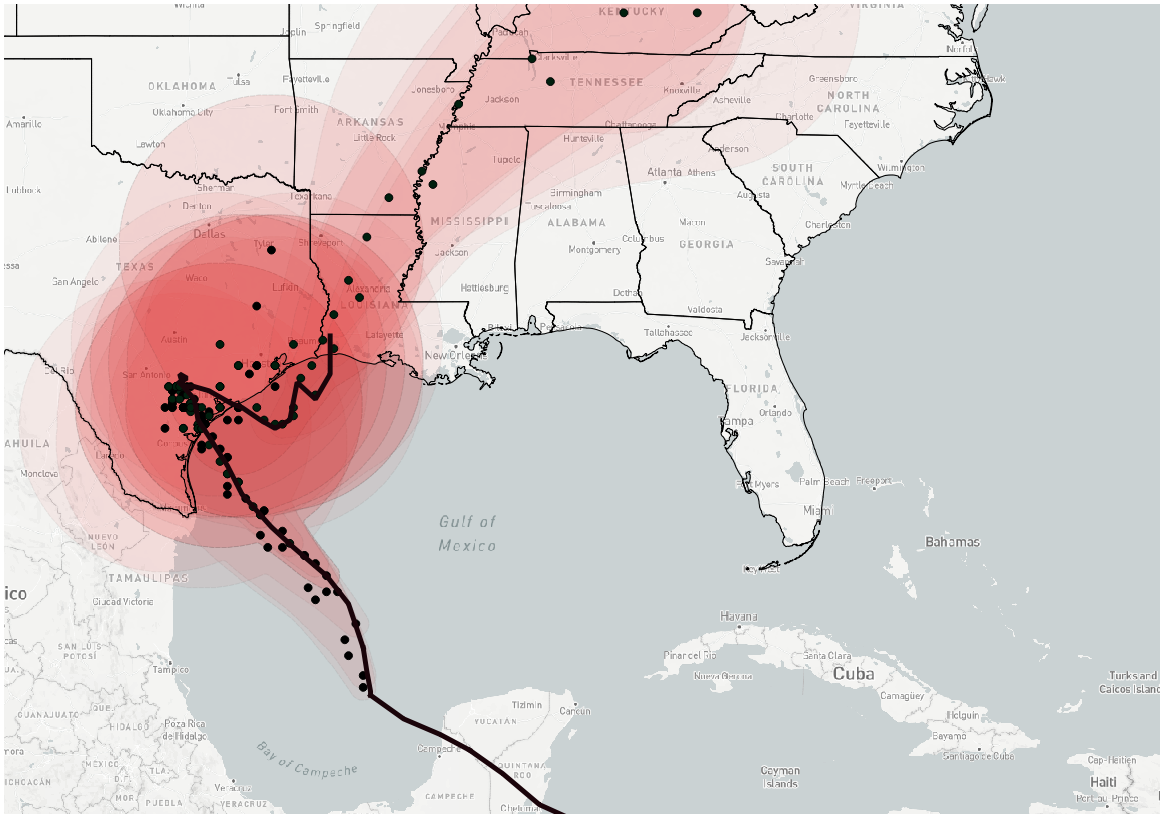

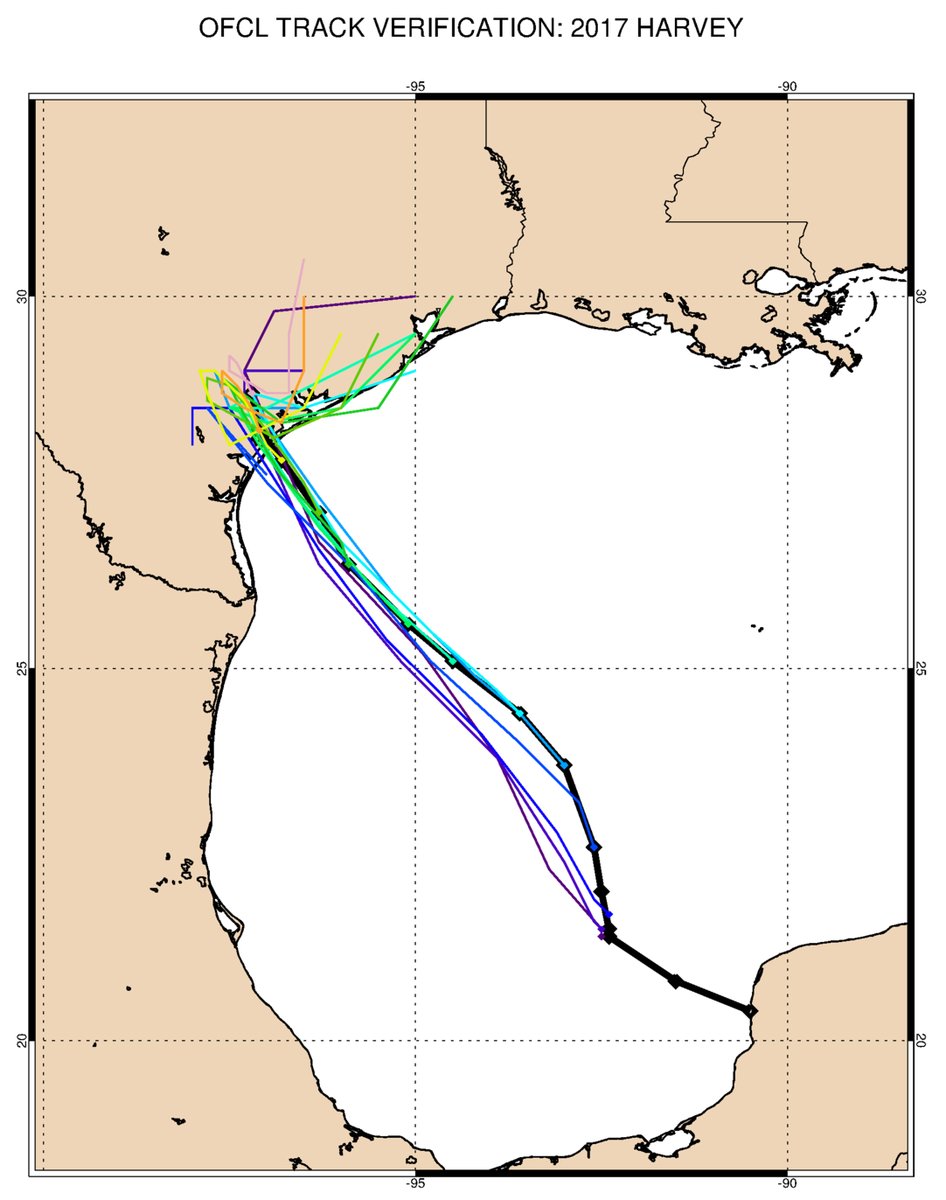

Below you can see all of the forecast cones for Harvey after redevelopment in the Gulf of Mexico. Each point represents the forecast track center corresponding to each NHC forecast cone at a valid forecast time, or every six hours. Finally, the solid black line is the actual track of Harvey through Wednesday morning, August 30th.

As you can see, there was great forecast certainty and consistency with each forecast issued by the NHC, nearly all of them taking Harvey into Texas northeast of Corpus Christi, with less certainty after landfall (wider array of dots):

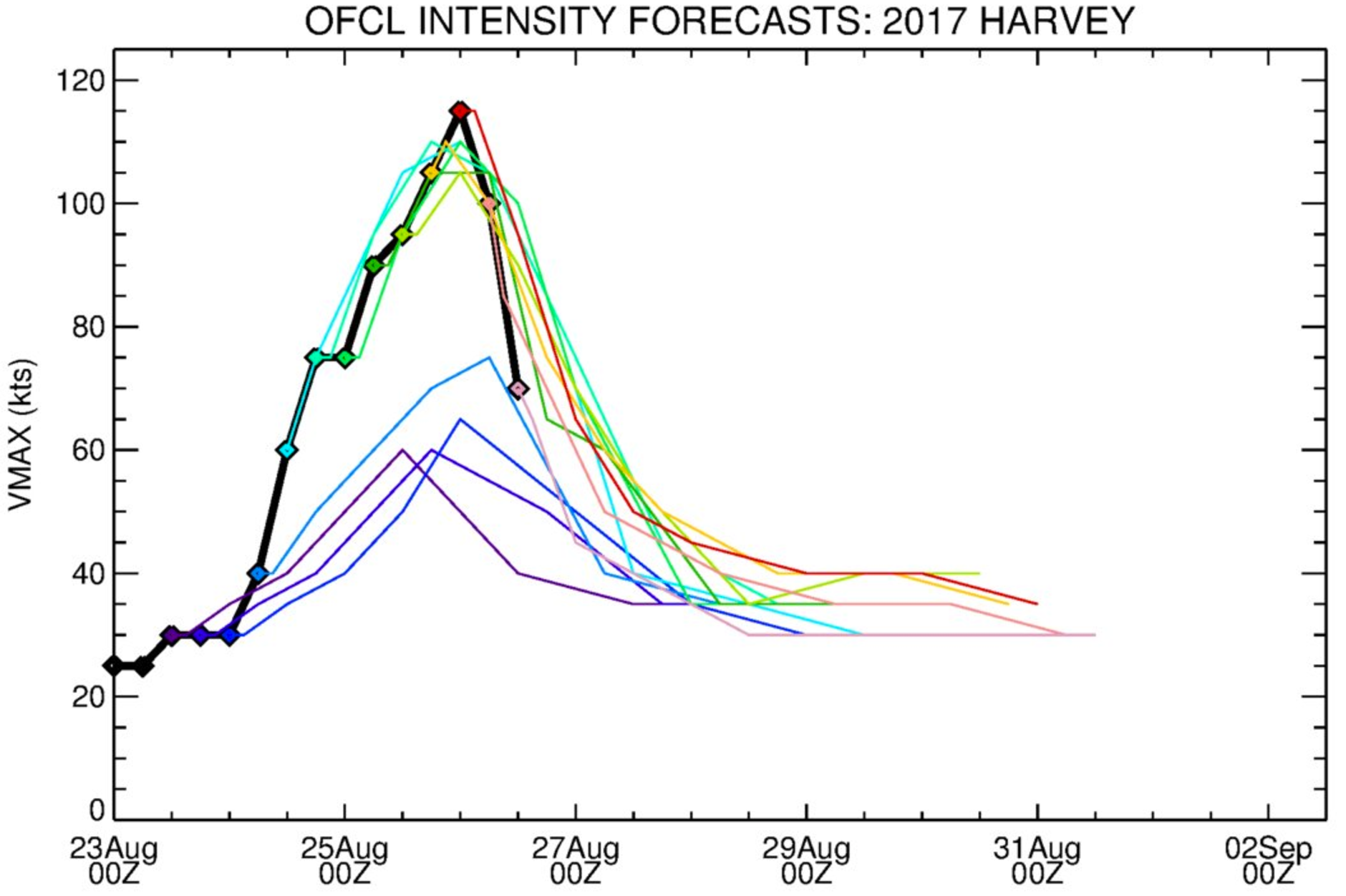

It's easier for forecasters to accurately forecast a storms track and speed than it is intensity. As we read above, the NHC latched onto a rapid intensification of Harvey quite quickly as it began to reorganize in the Gulf during the middle of last week.

Brian McNoldy shared the graphic below, which shows NHC intensity forecasts for Harvey after it entered the Gulf. Tropical storm intensity remains one of the bigger challenges to forecast accurately well in advance, especially when a storm undergoes rapid intensification. The graph below shows some of the early forecast from the NHC remaining too weak after Harvey reemerged in the Gulf, but then quickly we see the hurricane center recognize the potential RI and dramatically increase their forecast intensities:

Similarly, here are the official forecast tracks from the NHC, and the actual path (black) for comparison. Well done.

An improving NWP

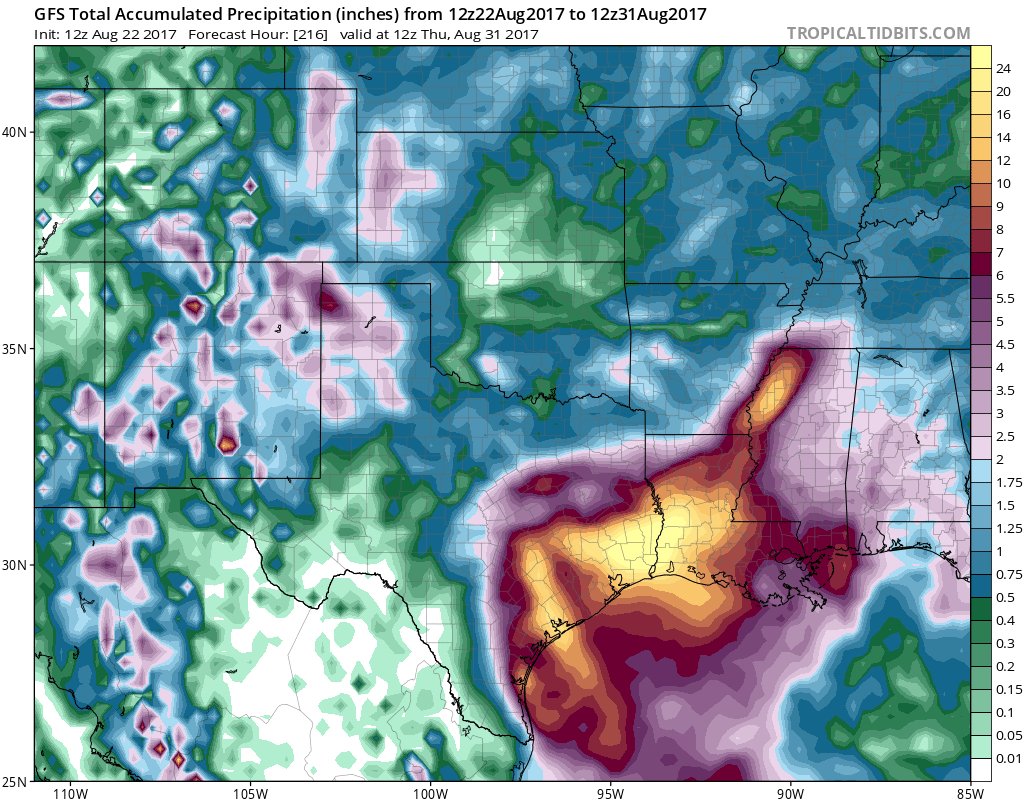

Weather modeling with Harvey was impressive. We had global models sniffing out this extreme event out well in advance, with many of the more bullish rainfall forecasts from models actually panning out. Here's the GFS rainfall forecast from early last week through this coming Thursday – forecasting (accurately) upwards of 24" across southeast Texas (h/t Sam Lillo):

And here's an early track forecast from the GFS, showing a long-lasting, looping tropical storm that would eventually devastate southeast Texas. The details would change, but a good idea early on:

GFS 12z solution for #Harvey is an epic deluge as system meanders through SE Texas for many days. Flooding obviously major concern. pic.twitter.com/b13ge4jIoR

— Ryan Maue (@RyanMaue) August 23, 2017

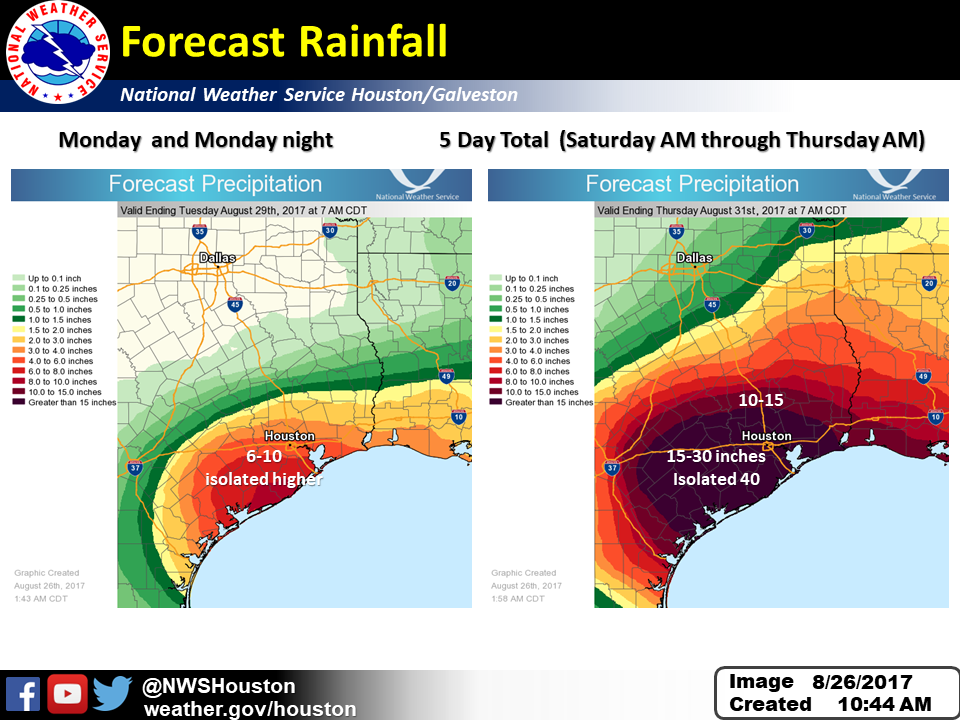

In some cases, meteorologists hedged too low with their rainfall forecast numbers despite weather models often accurately forecasting this extreme. While we can debate whether or not it's time to start putting more faith in the modeled data, here's why this is not an issue: forecasters instead focused on impacts with Harvey, and placed an urgency in their forecast briefs for this event rarely seen. Whether a particular station saw the 35" forecast, or the obscene 50" we saw fall in a few locales, at a certain point becomes irrelevant. The impacts from Harvey (wind, storm surge, and extreme rainfall) were all forecast quite well and very directly.

Related: The ABCs of NWP

Seeing is believing

For most, when whether forecasters are calling for 25" or 50" of rain, comprehending what exactly that means and looks like is virtually impossible, and this was likely the bigger issue in trying to make preparations for Harvey. We're talking about rainfall totals in a matter of days that a good chunk of this country won't see in years, and that's not easy to fathom. There's also an eagerness to discredit anything professionals tell us these days in the hunt for something that fits our way of thinking.

This, of course, is absurd, and often enough downright dangerous. It can can lead to confusion as to how bad any given event may actually be, and cause confusion as to what actions need to be taken in preparation for said event. While forecasters at the National Weather Service in Houston were busy trying to put out the word of the remaining extreme rainfall threat on Saturday morning, viral Facebook posts were spreading false information – with sometimes 100x more shares on social media than the official outlooks by the NWS, like the one (outlining additional rainfall as of Saturday morning) below:

While it's fair to struggle to wrap one's head around an event like this before it actually happens, let this be a lesson in the power of the tools and knowledge we have accumulated over the years, and instead of constantly sowing the seed of doubt, use this knowledge to better prepare for the next time.

TODO: Find a group of trusted, local-to-you meteorologists, and then follow them the next time a storm threatens your home and family rather than a troll account on Facebook.

Look, there will be plenty of discussion in the coming weeks surrounding what was done right and what could be improved the next time around with preparedness and recovery – like "should Houston have been evacuated?" (probably not). When it comes to weather forecasters, however, we talk a lot about failures of meteorologists and their (at times) inability to clearly communicate hazards around big weather events, as well as the rather endless "what we got wrong" think pieces. In Harvey, this should not be the case. This is not only a great example of a very well executed forecast of a slow, historic rainfall event (and major hurricane), but also a refreshing pile of examples of meteorologists issuing accurate, clear, and timely warnings about the serious threat Harvey posed.

So, to those meteorologists out there who were tasked with the incredible challenge of forecasting this devastating storm – often in their own back yard – kudos.

– NWS Aug 27, 2017